Archive for November, 2005

-

Buffett Unplugged

Eddy Elfenbein, November 14th, 2005 at 10:25 amThe Wall Street Journal looks at Warren Buffett. From this article, I’m surprised by how much Buffett leaves his managers alone. As he puts it, “we delegate almost to the point of abdication.” Here are some Buffett tips for individual investors:

-

Has the Santa Rally Started?

Eddy Elfenbein, November 14th, 2005 at 9:53 amThanks to a nice rally over the past two weeks, the market is right at the upper bound of a frustrating trading range. Every time the index has reached this level, it’s fallen back. We’re now about 1% away from a four-year high.

I’m curious if we’ll finally be able to break out. The market is set to open slightly lower today. I’m inclined to think we won’t break out just yet since the volatility index is still so low, but that’s just a hunch. I’m still rooting for this market.

There’s yet another company going private and this time, it’s a big one. Koch Industries is buying out Georgia Pacific (GP) for $13 billion. Sheesh…no one wants to be on the market anymore! This deal will make Koch the largest private company. Koch is run by Charles and David Koch, the sons of the founder. The brothers have been very active in libertarian circles. In fact, David was the Libertarian Party’s veep nominee in 1980 when the ticket got nearly 1 million votes.

The good news is that the consumer is still happy. Lowe’s (LOW) reported very good earnings this morning. The company topped expectations by four cents a share. Wal-Mart (WMT) reported earnings inline with expectations. The company averaged over $800 million in sales a day for the quarter.

This week is also the time for inflation reports. Wholesale prices come out tomorrow, and consumer prices follow on Wednesday. Thanks to plunging oil, we’ll probably see the biggest drop in inflation in decades. The market, however, will be more focused on “core inflation,” which is inflation minus volatile food and energy prices. As usual, I don’t expect much news here.

Also, AIG (AIG) is set to report earnings. The stock has been rebounding, but given its earnings restatement, and restatement of the restatement, I have no idea what to expect. -

The Airline Boom?

Eddy Elfenbein, November 13th, 2005 at 5:56 pmAccording to The Economist: “After losing $43 billion in five years, airlines are at the beginning of a massive boom.”

(T)he airline industry is poised for an almost unprecedented boom, as a new generation of planes is combining with better business models and huge volume growth in new markets. This year an industry with revenues of about $400 billion will end up paying $97 billion for its fuel. According to IATA (the International Air Transport Association), had the price of oil stayed where it was in 2003, at $30, instead of rising to the average $57 expected for the whole of this year, the world’s airlines would have made more profit ($45.6 billion) than they have lost in the past five years. (This, says IATA, is also partly a result of a 34% improvement in labour productivity.)

But there is more to it than savage cost-cutting; traffic volumes are growing. International traffic has risen by 8.3% so far this year, compared with 2004. In America, total traffic is up by 5.4%; in Europe the rise is 6%. In Asia, IATA is forecasting continuing annual growth of 6.8% through to 2009: China and some east European countries will go on growing by around 10%. -

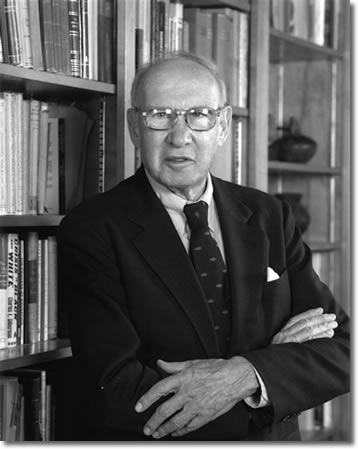

Peter F. Drucker 1909-2005

Eddy Elfenbein, November 12th, 2005 at 12:04 pmHe was born in Vienna during the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph (his middle initial F. stood for Ferdinand). Keynes and Schumpeter were his economics professors. His first book was reviewed by Winston Churchill in the Times Literary Supplement in 1939. The 29-year-old proved to be more prescient than the Great Man.

Mr. Drucker is one of those writers to whom almost anything can be forgiven because he not only has a mind of his own, but has the gift of starting other minds along a stimulating line of thought. There is not much that needs forgiveness in this book, but Mr. Drucker tends to be carried away by his own enthusiasm, so that the pieces of the puzzle fit together rather too neatly. It is indeed curious that a man so alive to the dangers of mechanical conceptions should himself be caught up in the subordinate machinery of his own argument. His proof, for example, that Russia and Germany must come together forgets the nationalism which has developed in Russia during the last twenty years and which would react very strongly against any new German domination of Russian life. But such excesses of logic are pardonable enough in a book that successfully links the dictatorships which are outstanding in contemporary life with that absence of a working philosophy which is equally outstanding in contemporary thought.

Within three months, Poland’s fate was sealed. When looking at Drucker’s work, the most arresting fact isn’t how much he got right, but how much he’s still misuderstood.

Mr. Drucker thought of himself, first and foremost, as a writer and teacher, though he eventually settled on the term “social ecologist.” He became internationally renowned for urging corporate leaders to agree with subordinates on objectives and goals and then get out of the way of decisions about how to achieve them.

He challenged both business and labor leaders to search for ways to give workers more control over their work environment. He also argued that governments should turn many functions over to private enterprise and urged organizing in teams to exploit the rise of a technology-astute class of “knowledge workers.”

Mr. Drucker staunchly defended the need for businesses to be profitable but he preached that employees were a resource, not a cost. His constant focus on the human impact of management decisions did not always appeal to executives, but they could not help noticing how it helped him foresee many major trends in business and politics.

He began talking about such practices in the 1940’s and 50’s, decades before they became so widespread that they were taken for common sense. Mr. Drucker also foresaw that the 1970’s would be a decade of inflation, that Japanese manufacturers would become major competitors for the United States and that union power would decline.

For all his insights, he clearly owed much of his impact to his extraordinary energy and skills as a communicator. But while Mr. Drucker loved dazzling audiences with his wit and wisdom, his goal was not to be known as an oracle. Indeed, after writing a rosy-eyed article shortly before the stock market crash of 1929 in which he outlined why stocks prices would rise, he pledged to himself to stay away from gratuitous predictions. Instead, his views about where the world was headed generally arose out of advocacy for what he saw as moral action.

As for me, I’m a bit weary of the Cult of Drucker, which is often quite different from the man. I often hear his disciples pontificate his “ideas,” which wind up being little more than Benjamin Franklin-style truisms—only covered in jargon and masquerading as ideology. “An apple a day keeps the doctor away” becomes “pro-active management encourages and facilitates preventative-based strategies in order to ensure long-run objectives without negative and unforeseen downside effects.” So much Latin, and so little English. Such are the dangers in thinking outside one’s box.

But how far can the study of management go? For all of management’s influence, the most difficult question is: Why is this enterprise worth managing? My fear is that Drucker’s legacy is so liquid that his mantle can be claimed by most anyone. The race has been on for quite some time. Right now, the yellow-jersey belongs to Newt Gingrich. The former Speaker of the House, who’s an admirer of Alvin Toffler and other future babble, has clearly adopted Drucker as a political ally.

Too many of our business schools, academic centers, media moguls, and government leaders still rely on the Keynesian command-and-control bureaucratic model. They rely on almost nothing of Drucker and even less of the Austrian school and, as a result, routinely apply the wrong principles to structuring education, training, health care, and our role in international trade. Again and again they reject the marketplace. They reject the principles of management. They reject the essence of entrepreneurship. They reject the heart of Drucker and apply instead patterns and behaviors that simply don’t work.

That is the ultimate critique of big-city schools. It’s the ultimate critique of government-run health care. It is the ultimate critique of the way the federal government and state and local governments mismanage resources. It simply doesn’t work.

To be sure, Gingrich’s ideas can stand or fall on their own—with or without the support of Drucker. But we ought to be cleat that Drucker’s ideas have little to do with what Gingrich says. In fact, Drucker was never particularly interested in economics. Too much theory, not enough people.

Drucker’s concern was studying institutions as institutions. That’s what he saw in 1939. The Nazis and Soviets had to come together. It was simply what they were. The institutions demanded it. For Drucker, it didn’t matter which institutions he looked at; governments, unions, corporations. He really didn’t find much use in analyzing the government. Drucker preferred the non-profit sector. He even looked at the girl scouts. To Drucker, an institution had an internal agenda simply because it is an institution.

Drucker saw the driver of an institution as its management. His goal was to isolate management as a separate concept and study what made some managers good, and others bad. While it sounds a bit platitudinal now, it was quite new then.

Still, when reading Drucker I can’t help feeling undernourished. Consider this from Forbes a few years ago:

In 1989 C. William Pollard, chairman of the ServiceMaster Co., took his board of directors from Chicago to meet Drucker. In a back room of Drucker’s utterly unpretentious home, the sage of Claremont opened the meeting by asking the group, “Can you tell me what your business is?”

Each director gave a different answer. Housecleaning, said one. Insect extermination, said another. Lawn care, said a third.

“You’re all wrong,” Drucker said. “Gentlemen, you do not understand your business. Your business is to train the least-skilled people and make them functional.”

Groan. This is only the beginning of an exposure to Drucker. Soon, the “ideas” begin to flow freely. We’re now “knowledge workers.” And we’re moving to a “knowledge-based society.” But…what of it? Before we know it we’re “managing change,” yet I’m only interested in “making money.” Again, here’s Drucker:

One of the most important jobs ahead for the top management of the big company of tomorrow, and especially of the multinational, will be to balance the conflicting demands on business being made by the need for both short-term and long-term results, and by the corporation’s various constituencies: customers, shareholders (especially institutional investors and pension funds), knowledge employees and communities.

Call me unimpressed. I can’t say that I disagree with anything Drucker says, which is part of the problem. Truthfully, I think the study of management can only go so far. It’s important, but it’s easily overanalyzed. Just as the diplomat urges diplomacy and the general favors war, the management guru sees only the primacy of managers. To the Drucker’s fans, it’s seems hard to conceive the fact that Grant crossed the James without the aid of a flow chart.

Here’s a large section of Druckerama. Apparently, everything is transformational. Everyone is empowered. It all sounds so epic, yet at the same time so…bland. The themes have taken over the building and they’ve smothered the plot. What’s left is Drucker’s true legacy, his boundless enthusiasm. If only all managers had it. To Churchill, Russia may have been riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, but he saw Drucker clearly.

-

The Market Today

Eddy Elfenbein, November 11th, 2005 at 4:25 pmWell, heck. November’s turning out to be a pretty good month. The Buy List is already up 5.18% for the month while the S&P 500 is up 2.30%. Today, the Buy List added another 0.45% and the S&P was up 0.31%. I knew we could outsmart the robots.

The bond market was closed for Veteran’s Day, and the stock market was very quiet. One surprise is that Commerce Bancorp (CBH) was out top performer. CBH added 4.0% today even though the stock was downgraded yesterday by A.G. Edwards.

Here are a few links that I found interesting. One of my favorite bloggers, Michelle Leder of Footnoted.org, found this gem:How often do top executives agree to forgo their bonuses? About as frequently as pigs fly. Which is why this 8-K filed by The Banc Corporation (TBNC) this week is particularly amusing. In a press release, the company notes that the three top executives “will not accept any performance bonus for which they might have been eligible for” which works out to about $450K for the three. But here’s the clincher: the board has agreed to accelerate the vesting of 625,942 options held by the three — options that are worth about $2 million.

There’s a growing business for corporate sleuths. (Via: The Kirk Report.)

Dell’s CEO talks to Business Week.

Value investing is still winning.

And Zimbabwe’s inflation is running at 411%. A month. -

Program Trading Accounts For 56.7% of NYSE Volume

Eddy Elfenbein, November 11th, 2005 at 3:20 pmI find this a little unnerving. Odds are, the last stock I bought was from C3PO:

Program trading in the week ended Nov. 4 accounted for 56.7%, or an average of 1.08 billion shares daily, of New York Stock Exchange volume. Brokerage firms executed an additional 742.7 million daily shares of program trading away from the NYSE, with 1.4% of the overall total on foreign markets. Program trading is the simultaneous purchase or sale of at least 15 different stocks with a total value of $1 million or more.

Of the program total on the NYSE, 7.6% involved stock-index arbitrage. In this strategy, traders dart between stocks and stock-index options and futures to capture fleeting price differences. Less than 0.1% involved derivative product-related strategies. Index arbitrage can be executed only in a stabilizing manner when the Dow Jones Industrial Average moves 150 points or more from its previous day’s close.

Some 53.7% of program trading was executed by firms for their clients, while 40.3% was done for their own accounts, or principal trading. An additional 6.1% was designated as customer facilitation, in which firms use principal positions to facilitate customer trades.

Of the five most-active firms overall for the week, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.’s Lehman Brothers Inc. and UBS AG’s UBS Securities LLC executed most of their program trading as principal for their own accounts. Deutsche Bank AG’s Deutsche Bank Securities, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., and Morgan Stanley executed most of their program trading activity for customers, as agent.Today’s a pretty quiet day on Wall Street. The bond market is closed for Veteran’s Day. The stock market’s volume is very low. There’s not much news from our Buy List. Dell (DELL) is trading up about 1%. St. Jude Medical (STJ) just got approval to buy Advanced Neuromodulation Systems (ANSI). For the record, this is not a mega-merger. St. Jude is more than 10 times as large as ANSI.

The Dow is within striking distance of 10700. The index has closed between 10200 and 10700 for 125 of the last 126 sessions. -

Thoughts on Dell

Eddy Elfenbein, November 11th, 2005 at 6:15 amYesterday was D-Day—Dell reported earnings. At this point, Dell’s image among the financial media is somewhere between Kim Jong-il and thyroid cancer.

If you recall, on Halloween Dell said it was going to report earnings of 39 cents a share, which was at the “low-end of expectations.” The media went into gleeful outrage and fell beneath the low-end of my expectations, which—let’s face it—is already pretty darn low. As for Dell’s stock, it promptly dropped 8% on volume of 105 million shares. Apparently, the low-end of expectations was…well, not expected.

Speaking of low-end, that’s the rap against Dell. The company can’t compete in the market for cheap PCs. Plus, their sales growth is slowing, their customer service is horrible and they’re pursuing nuclear weapons. No wait, that last one I think is Kim Jong-il. But you get the idea.

Over the last few days, I’ve gotten about 20 gabillion e-mails asking me why I’m not panicking over Dell. The easy answer is that panicking won’t make me any money. (I’ve tried it.) The other reason I’m not panicking is that there’s no reason to panic.

The Major Concern right now is Dell’s slowing sales growth. For the last several quarters Dell’s sales growth has slowed down (or “decelerated” if you’re an analyst, or maybe a Vulcan). But slowing sales growth is not necessarily a problem.

Here’s your investing lesson for today. When you’re looking at a company, the single-most important number is return-on-equity. Forget head-and-shoulders, forget bear traps and double bottoms, forget volume, forget stochastics. Return-on-equity tells you more than anything else about how well a company is performing. It’s the best measure of efficiency, bar none. In short, ROE tells us how much we get for how much we got.

ROE can be deconstucted down into three parts (warning, math ahead). Profits margins, asset turnover and leverage. Think of it this way:

Profit margin is profits divided by sales.

Asset turnover is sales divided by assets.

Leverage is assets (stuff you have) divided by equity (stuff you own).

If we multiply them it will look like this:

(Profits) (Sales) (Assets)

———- X ——-X——– = ROE

(Sales) (Assets) (Equity)

I pass the graphics savings on to you.

The mathematically inclined will see that the two “sales” and two “assets” cancel each other out. And we’re left with profits divided by equity, or return-on-equity. See, easy.

The beauty of ROE is that it works for every company. You can compare General Electric to a lemonade stand. A company like Wal-Mart may have a teeny profit margin (around 3%), but incredible asset turnover. Wal-Mart is really just one big inventory control machine. A financial company like Citigroup might have 15 or 20 times more assets than equity, but it generates only a few pennies of revenue for each dollar of assets.

Everything here balances out. If you want to borrow more to increase your leverage, your interest costs will hurt your profit margin. Or, you can increase your asset turnover by lowering your margins. Doesn’t this just scream for its own School House Rock? (R-O-E for you and me!)

Return-on-equity doesn’t lie, and it can’t be tricked. Earlier this year, General Motors generated huge sales growth with its employee discount. But it sacrificed its profit margins. The ROE never changed. GM just rearranged the equation. It turns out, GM still sucks.

The other great thing about ROE is that it’s stable. Almost all financial stats can bounce around, but the ROE of a company tends not to change much from year-to-year. The only true way to improve your ROE is to become more efficient.

The ROE of your average company is about 10%. The good ones are around 15%. Really good is 18%-20%. Yesterday, I talked about Patterson Companies. Patterson has had nine straight years of over 20% ROE. It could be longer—that’s as far back as my records go. For the last six years, Dell has averaged 40% return-on-equity.

Now do you see why I give Dell the benefit of the doubt?

For the third quarter, Dell increased its revenues by 11.3%. But thanks to a shift to higher-margin products, the company was able to increase its net margins. Dell isn’t getting beaten on the low-end. It’s changing its strategy so it’s not so reliant on the low-end. The ROE for was over 18% for last quarter alone. (I haven’t dug through the details, but it looks like Dell’s equity was hurt by a bad investment, which lowers the equity base.)

So let’s look at the scoreboard. Dell’s stock is $13 off its high. Yet, if it hard earned two more pennies a share this quarter, no one would be complaining. Two pennies versus $13? So those marginal pennies had a P/E ratio of 650! Yes, I have no problem taking the other side of that bet.

By the way, Dell grew its earnings-per-share by nearly 17% last quarter. This is the disaster we’re looking at? Now look at any old story from the last two weeks. We have “It’s Bad to Worse at Dell” from, where else, Business Week. This comes a few weeks after the magazine ran two anti-Dell pieces simultaneously. Every blackheart’s favorite story is: The King Is Dead.

Maybe Dell is done for, but they have a funny way of showing it. My theory is that bad news sticks to them. And for now, I’m sticking with ’em too. -

The Market Today

Eddy Elfenbein, November 10th, 2005 at 4:37 pmFinally, a strong day for the market! The S&P 500 is at its highest level in two months. Our Buy List had a solid day across the board. While the S&P 500 gained 0.84%, the Buy List was up 1.82%. Twenty-three stocks were up and only two were down. Today’s big winner was Golden West Financial (GDW) which jumped 5.2%. We also got nice returns from Progressive (PGR) and Quality Systems (QSII).

We got new highs from AFLAC (AFL), Fair Isaac (FIC) and St. Jude (STJ). Varian Medical (VAR) is oh-so-close to a new high. Commerce Bancorp (CBH) was downgraded by A.G. Edwards, but it still managed to close higher.

Outside our Buy List, Intel (INTC) announced a huge $25 billion share buyback, plus a dividend increase. I’d prefer to see companies pay out dividends rather than buy its own shares. If investors want to buy more shares, that should be their choice. Companies should be in charge of operations; investors should be in charge of profits. Several companies are loaded up with cash. Cisco (CSCO) has $14 billion and Microsoft (MSFT) has nearly $50 billion. In fact, Wall Street was expecting a dividend from Cisco yesterday but the company balked.

Today was also D-Day. Dell’s (DELL) earnings came out after the close. The Street hated its last earnings report, plus the company guided lower a few days ago. Every financial media outlet has pounded on the company, and the shares fell below $29.

The company just reported earnings of 39 cents a share which was in line with its reduced estimate. Sales were $13.9 billion, slightly below expectations. For next quarter, Dell said it will earn between 40 and 42 cents a share, and revenue will be between $14.6 billion and $15 billion. The company is also buying back $1.7 billion worth of stock.

The knock on Dell has been that it’s focusing on the high-end, while its competitors are hurting it on the low-end. I think these criticisms are very much over-rated. Kevin Rollins, the CEO, has said that Dell has to have a balance between the high- and low-end. Plus, margins are much better on the high-end.

Lemme see…a record trade deficit is announced, the dollar rallied and 10-year bond had one its best auctions in years. Pardon me while I burn all my economics books. The bond market actually dragged the entire stock market higher.

General Motors (GM) plunged to a 23-year low. The stock is lower than where it was when Ralph Nader took on the Corvair 40 years ago. Two other things to mention: Seeking Alpha has a great collection of conference call transcripts. Also, Booyahboy Audit is tracking Jim Cramer.

Also, please feel free to e-mail me at eddy@crossingwallstreet.com. I’m going to start a regular Q&A feature on the Web site. -

A Loophole for Hedge Funds

Eddy Elfenbein, November 10th, 2005 at 3:31 pmNext year, hedge funds have to register with the SEC. Funds will also have to provide more information, plus they’re subjected to periodic audits. However, there’s one loophole that many funds are using.

But the SEC’s rule only applies to advisors that permit investors to redeem their interests in a hedge fund within two years of purchasing their stakes. The agency concluded that the average “lockup” period for hedge funds is 12 months, so the 12-month period is the time frame covered by the rule.

“We’re aware that some hedge-fund advisers are planning to extend their lockup period and we’ll evaluate the situation when we have a better picture of the situation in February,” said Robert Plaze, associate director of the SEC’s investment-management division. However, the SEC’s registration rule proved quite contentious, even within the agency, so in the near term it may be difficult for the SEC to adjust the rules to capture the lockup extenders.

Some of the largest firms, like SAC, with $6.5 billion under management, and Kingdon, are in the process of instituting longer-term lockups. Others, such as Lone Pine, which manages $6.9 billion, aren’t open to new investors and don’t need to register. Citadel, a $12 billion firm, and Eton Park, which manages $3 billion, have always featured long-term lockups for the bulk of their money, so the SEC’s rules don’t apply.It’s difficult to regulate an industry that was created specifically to avoid regulation. The hedge funds will play every angle.

“We have seen a rise in the number of firms asking for two-year lockups and the driver of that is probably the SEC requirements,” says Thomas Schneeweis, director of the Center for International Securities and Derivatives Markets at the University of Massachusetts. “If you can pull it off, let’s face it, you’d do it.”

So far, the anticipated flood of new registered investment advisers has yet to materialize. An estimated 5,000 or so of the approximately 8,000 existing hedge funds aren’t yet registered. So far this year, however, new registrations average about 100 a month, according to SEC data, not much more than last year’s 80-a-month pace. -

Industry Groups Over the Long Term

Eddy Elfenbein, November 10th, 2005 at 2:52 pmProfessor Ken French is a well-known finance professor at Dartmouth. At his Web site, he keeps an impressive data library. One of the items that I like to look at every few months is the how certain industry groups have performed over the long run. Here’s the annualized return for several industry groups for the past eight decades.

Smoke 13.69%

Beer 13.51%

Banks 12.80%

Drugs 11.93%

Hardw 11.45%

Aero 11.37%

Oil 11.33%

Food 11.28%

Chips 11.22%

Meals 10.99%

Chems 10.91%

Boxes 10.84%

Fin 10.64%

Mines 10.53%

Rtail 10.49%

MedEq 10.40%

Autos 10.38%

Mach 10.33%

Insur 10.21%

Coal 10.16%

ElcEq 10.06%

Other 9.95%

Clths 9.83%

Hshld 9.78%

BldMt 9.67%

Telcm 9.31%

Books 9.23%

BusSv 9.10%

Util 9.08%

Ships 8.97%

LabEq 8.87%

Fun 8.76%

Steel 8.45%

Trans 8.41%

Txtls 7.94%

Cnstr 7.91%

Agric 7.83%

Toys 7.45%

Whlsl 5.54%

RlEst 3.86%

I guess vice is far more profitable than virtue, which I kinda suspected.

-

-

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His