Archive for September, 2007

-

Chart of the Day

Eddy Elfenbein, September 19th, 2007 at 7:37 amLeucadia National Corporation (LUK) compared with the S&P 500:

-

50 Points!

Eddy Elfenbein, September 18th, 2007 at 2:16 pmThe Federal Open Market Committee decided today to lower its target for the federal funds rate 50 basis points to 4-3/4 percent.

Economic growth was moderate during the first half of the year, but the tightening of credit conditions has the potential to intensify the housing correction and to restrain economic growth more generally. Today’s action is intended to help forestall some of the adverse effects on the broader economy that might otherwise arise from the disruptions in financial markets and to promote moderate growth over time.

Readings on core inflation have improved modestly this year. However, the Committee judges that some inflation risks remain, and it will continue to monitor inflation developments carefully.

Developments in financial markets since the Committee’s last regular meeting have increased the uncertainty surrounding the economic outlook. The Committee will continue to assess the effects of these and other developments on economic prospects and will act as needed to foster price stability and sustainable economic growth.

Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman; Timothy F. Geithner, Vice Chairman; Charles L. Evans; Thomas M. Hoenig; Donald L. Kohn; Randall S. Kroszner; Frederic S. Mishkin; William Poole; Eric Rosengren; and Kevin M. Warsh.

In a related action, the Board of Governors unanimously approved a 50-basis-point decrease in the discount rate to 5-1/4 percent. In taking this action, the Board approved the requests submitted by the Boards of Directors of the Federal Reserve Banks of Boston, New York, Cleveland, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Kansas City, and San Francisco. -

The Importance of Interest Rates

Eddy Elfenbein, September 18th, 2007 at 1:24 pmIf you’re new to investing or if you’re simply curious as to why us bloggers jabber on incessantly about the Federal Reserve and interest rates, it’s because it’s hard to overemphasize the importance of interest rates on equity valuations.

Understanding this fact is one of the most important keys to investing. Simply put, interest rates call the shots for the stock market. Not only do lower rates make it cheaper to rent someone else’ money, but it also provide stiffer competition for stock prices so shares tend to adjust higher. When rates rise, the opposite happens. I’ll give you an example. I looked at all the data going back to 1962. I separated out each day that short-term T-bill rates fell. I then squished all those days together and found that combined, the S&P 500 rose over 2,000%. On days when rates rose—a nearly identical time frame—the S&P lost nearly 60%. As impressive as that it, for long-term rates, the effect is even more dramatic. On days when the 10-year T-bond yield fell, the S&P soared 90,000%. Wow! On days when the yield climbed, the S&P 500 dropped nearly 99%. If we try to annualize that, assuming 253 trading days year, that means the S&P gains 42.3% a year when long-term rates fall and it loses 20.4% when long-term rates rise. We can put those two variables together and see how the stock market reacts to the spread between short-term and long-term rates. Not surprisingly, stocks like a positive yield curve (when short rates are less than long). When the yield curve is positive (about 87% of the time), the S&P 500 gained 2,500%. When the yield curve is negative, stocks are down about 25%. Here’s the kicker: All of the S&P 500’s price gains have come when the yield curve is positive by 67 or more basis points. Anything less than that, stocks have flat. Zippo. One more thing. The current spread is about 45 basis points. -

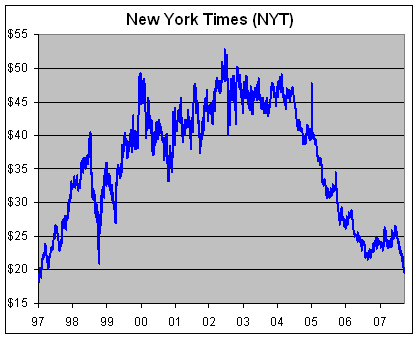

The New York Times Hits a 10-Year Low

Eddy Elfenbein, September 18th, 2007 at 10:03 am

-

Greenspan’s Genius

Eddy Elfenbein, September 18th, 2007 at 9:29 amElizabeth Spiers looks at the Maestro:

Americans have a long history of confusing inscrutability with genius. The less you say, the conventional wisdom goes, the smarter people will think you are. Alan Greenspan, the most powerful Fed chairman in history, built his storied career on this simple, if shaky, premise. His memoir, The Age of Turbulence, will be published this month, and it will be interesting to see how he stretches this rhetorical formula across 640 pages. Greenspan’s particular style has always been to offer a short restating of the facts that are obvious to most economic observers, peppered with a few original insights that can be interpreted as black, white, or a blackish-whitish shade of gray, depending on who’s listening. In Greenspanish, two and two may equal four. But it may also equal two discrete sets of two that shall never become four. And that assumes we all agree on how four should be defined. (If you find that analogy impenetrable, just make like a Greenspan acolyte and assume that it’s brilliant.)

-

Economic Myths

Eddy Elfenbein, September 17th, 2007 at 12:21 pmThis is a good time to repost this. In December, Nobel Prizer Edward Prescott listed five economic myths in the Wall Street Journal. Myth #1 is that monetary policy causes booms and busts:

One of the mysteries of the 1990s is how to explain the economic boom when the increase in capital investments — as measured by the national accounts — grew at a subdued pace. The numbers simply don’t add up. However, it turns out that something special happened in the 1990s, and it wasn’t monetary policy. In a recent paper, Minneapolis Fed senior economist Ellen McGrattan and I show that intangible capital investment — including R&D, developing new markets, building new business organizations and clientele — was above normal by 4% of GDP in the late 1990s.

This difference is key to understanding growth rates in the 1990s: Output, correctly measured, increased 8% relative to trend between 1991 and 1999, which is much bigger than the U.S. national accounts number of 4%. Associated with this boom in unmeasured investment is the huge amount of unmeasured savings that showed up in the wealth statistics as capital gains. This was the people’s boom, the risk-takers’ boom. We should hang gold medals around these entrepreneurs’ necks. So indeed, it does seem that Mr. Greenspan was lucky in that a boom happened under his watch; but we can at least say that he did a pretty good job of keeping inflation in check. Here’s hoping for the same performance from our current chairman. What about busts? Let’s begin with the assumption that tight monetary policy caused the recession of 1978-1982. This myth is so firmly entrenched that I could have called this downturn the “Volcker recession” and readers would have understood my reference. To accept the myth, you have to accept a consistent relationship between monetary policy and economic activity — and as we’ve just seen, this relationship is simply not evident in the data. Between 1975 and 1980, the inflation-corrected federal funds rate was low; at the same time, output trended upward until late 1978. So far, things look somewhat promising for the mythmakers. But looking closer at the data we see that output began its downward trend in late 1979 while monetary policy was still easy through most of 1980. Also, output continued its decline through 1982, when it began to climb at a time when monetary policy remained tight. These facts do not square with conventional wisdom. Our obsession with monetary policy in the conduct of the real economy is misplaced. One caveat: I am not saying that there are no real costs to inflation — there certainly are. And if we get too much inflation we can exact high costs on an economy (witness Argentina as an example). However, I am talking here of the vast majority of industrialized countries who live in a low-inflation regime and who are in no danger of slipping into hyperinflation. It is simply impossible to make a grave mistake when we’re talking about movements of 25 basis points. -

AOL Is Moving to New York

Eddy Elfenbein, September 17th, 2007 at 10:34 amI was always amused that AOL referred to its headquarters as being in “Dulles, Virginia.” Before it got that name, I tended to think of it as “that area way out by the airport.”

Well, no more. Start spreading the news: AOL is packing its bags and heading to NYC:AOL is moving its corporate headquarters from Dulles to New York, the company announced today, ending a saga that helped cement Washington’s identity as a technology center but also gave rise to corporate scandal and ill-fated dealmaking.

The company employs 4,000 people in Northern Virginia, and company officials said most will remain here. Senior executives, however, will be transferred to the company’s new headquarters at 770 Broadway in Manhattan.

The company, which abandoned its fee-for-service model as subscriptions declined and internet access was taken over by cable and telephone companies, said it is making the move to be closer to the center of the advertising industry that is now crucial to its survival. -

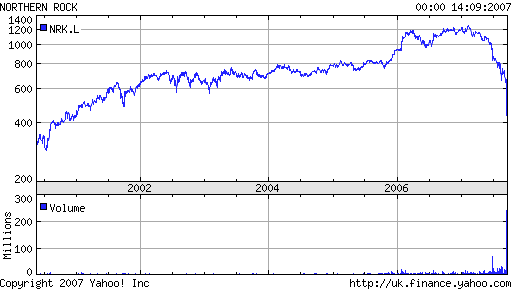

Northern Rock

Eddy Elfenbein, September 17th, 2007 at 10:28 amFor the past few days, depositors in Britain’s Northern Rock have lined up to withdraw their money. Now the government says it will guarantee all deposits.

Here’s how the stock has done:

-

Greenspan Unplugged

Eddy Elfenbein, September 17th, 2007 at 9:31 amAlan Greenspan is speaking this week at GW. I may go to see him, but I’m really not that interested. A few years ago, I would have jumped at the chance. Nowadays, I feel he’s just trying to defend his record, which is an increasingly difficult job.

One of the aspects I didn’t like of his tenure was how he made his views known on subjects not related to monetary policy. As I’ve said many times before, the Federal Reserve is far less important than most people realize. I think the fact that it’s so secretive helps keep the illusion alive.

Last night I saw Greenspan on 60 Minutes describe how he purposely gave incomprehensible answers to Congress. He worked hard at doing so. He and Lesley Stahl were giggling as if it were the cutest thing. It’s not.

Today’s WSJ has more from Greenspan:Mr. Greenspan was himself a behind-the-scenes advocate of overthrowing former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein. He says he felt “getting Saddam out of there was very important,” not because of weapons of mass destruction, but because he was convinced the Iraqi dictator wanted to control the Strait of Hormuz, through which a sizable portion of the world’s oil passes. That would enable him to threaten the U.S. and its allies. He said he conveyed that view to both Mr. Cheney and then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, another friend from the Ford administration, but doubts that played a part in the Bush administration’s decision to invade Iraq.

He recalls one administration official telling him such an argument couldn’t fly politically, which Mr. Greenspan assumed to mean because of Mr. Bush’s and Mr. Cheney’s background in the oil industry. Yesterday, Defense Secretary Robert Gates, appearing on ABC’s “This Week,” rejected the assertion in Mr. Greenspan’s book that the Iraq war “is largely about oil.” Mr. Gates said, “it’s about stability in the Gulf. It’s about rogue regimes trying to develop weapons of mass destruction.” -

Barney Frank on the Subprime Crisis

Eddy Elfenbein, September 14th, 2007 at 12:25 pmFrom the Boston Globe:

Well-functioning financial markets depend on transparency and confidence that institutions are playing by clearly defined rules. Both were in short supply in the months leading up to the August meltdown and remain so today. Large pools of unregulated capital, often highly leveraged, especially in hedge and private equity funds remain opaque and have been joined by massive sovereign investment funds to transform the financial landscape in ways that are out of reach of regulators here at home and in other wealthy countries. We lack the information that we need to ensure safety and soundness as well as the confidence that comes from the requirements mandating governance and reporting standards that apply to publicly traded companies.

To an important extent these new pools of capital are structured in a fashion that allows them to avoid the scrutiny that is required of firms and financial institutions in the regulated sectors. We should not be surprised. It is a fact of life that investors and firms will seek to innovate their way around whatever regulatory strictures apply, whether they deal with health and safety, labor protections, or reporting obligations. This tendency has been exacerbated by a 30-year attack on the very notion of a regulatory role for governments and loud professions that the market not only knows best, but knows everything.

Our job is to understand the changes in the financial marketplace and consider what we must do to ensure that our regulatory system is able to keep up with those changes. Innovation is as important in financial markets as it is in product markets, but it would be foolish to act as if regulatory structures, designed for a different world, do not have to be as nimble and innovative as those they regulate.

-

-

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His