Archive for January, 2009

-

Finger Length May Predict Financial Success

Eddy Elfenbein, January 13th, 2009 at 11:23 amI don’t even know what to say about this one:

The length of a man’s ring finger may predict his success as a financial trader. Researchers at the University of Cambridge in England report that men with longer ring fingers, compared to their index fingers, tended to be more successful in the frantic high-frequency trading in the London financial district.

Indeed, the impact of biology on success was about equal to years of experience at the job, the team led by physiologist John M. Coates reports in Monday’s edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The same ring-to-index finger ratio has previously been associated with success in competitive sports such as soccer and basketball, the researchers noted. -

Are You Born to Be a Trader?

Eddy Elfenbein, January 13th, 2009 at 11:04 amIt might depend on your level of testosterone:

A new study has found that men who were programmed in the womb to be the most responsive to testosterone tend to be the most successful financial traders, providing powerful support for the influence of the hormone over their decision-making.

“Testosterone is the hormone of irrational exuberance,” said Aldo Rustichini, a professor of economics at the University of Minnesota who helped conduct the study, being published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “The bubble preceding the current crash may have been due to euphoria related to high levels of testosterone, or high sensitivity to it.”

Although it may come as no surprise that testosterone could be a big player in the mano-a-mano world of Wall Street, the research offers the best evidence yet of the hormone’s role in determining which would-be Masters of the Universe will thrive. It also supports the growing recognition that biology plays a role in complex human behaviors, and that financial choices in particular are often less rational than economists appreciated.

“We have this idea that economic agents are like Spocks — they are just rational,” said John M. Coates of the University of Cambridge in England, who led the study. “This paper suggests the traders are surviving not so much because they are rational but because they have certain biological traits.”Yet another argument against the efficiency of markets.

BTW, I think Spock would make an excellent trader. That death grip thingy would really come in handy in the trading pits. -

Bernanke in London

Eddy Elfenbein, January 13th, 2009 at 10:19 amHere’s a snippet of the bearded one speaking at the London School of Economics:

One important tool is policy communication. Even if the overnight rate is close to zero, the Committee should be able to influence longer-term interest rates by informing the public’s expectations about the future course of monetary policy. To illustrate, in its statement after its December meeting, the Committee expressed the view that economic conditions are likely to warrant an unusually low federal funds rate for some time.2 To the extent that such statements cause the public to lengthen the horizon over which they expect short-term rates to be held at very low levels, they will exert downward pressure on longer-term rates, stimulating aggregate demand. It is important, however, that statements of this sort be expressed in conditional fashion–that is, that they link policy expectations to the evolving economic outlook. If the public were to perceive a statement about future policy to be unconditional, then long-term rates might fail to respond in the desired fashion should the economic outlook change materially.

Other than policies tied to current and expected future values of the overnight interest rate, the Federal Reserve has–and indeed, has been actively using–a range of policy tools to provide direct support to credit markets and thus to the broader economy. As I will elaborate, I find it useful to divide these tools into three groups. Although these sets of tools differ in important respects, they have one aspect in common: They all make use of the asset side of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. That is, each involves the Fed’s authorities to extend credit or purchase securities. -

Economics the 60 Minutes Way

Eddy Elfenbein, January 11th, 2009 at 8:33 pm

Watch CBS Videos Online

60 Minutes just ran a comically slanted story on the rise in oil prices. I know that the price of oil is now down by $100 a barrel over the past few months, but that doesn’t seem to matter when you’re in the alarmism business.The 60 Minutes story is wretched, incoherent and it engages in the worst form of scapegoating. It’s hard to believe that this made it to air.

According to 60 Minutes, the surge in oil prices was due to…(wait for it)…deregulation! Yes, it seems that “hedge funds” (cue Darth Vader’s theme) and “speculators” were buying oil in order to make money. If you just toss around these scare words long enough, people will think it makes sense. Somehow this was all due to deregulation. Of course, oil is traded all over the world, but logic doesn’t play a major role in this story.

First, Steve Kroft first talked with Dan Gilligan, the president of the Petroleum Marketers Association. Gilligan admitted that the members of his trade group, the people who pay his salary, are the ones responsible and he wouldn’t hear of anyone trying to shift the blame.

Kidding!“Approximately 60 to 70 percent of the oil contracts in the futures markets are now held by speculative entities. Not by companies that need oil, not by the airlines, not by the oil companies. But by investors that are looking to make money from their speculative positions,” Gilligan explained.

Gilligan said these investors don’t actually take delivery of the oil. “All they do is buy the paper, and hope that they can sell it for more than they paid for it. Before they have to take delivery.”

“They’re trying to make money on the market for oil?” Kroft asked.

“Absolutely,” Gilligan replied. “On the volatility that exists in the market. They make it going up and down.”Egad, speculators trying to make money! Next we’ll hear that other people buy things and “sell it for more than they paid for it.” Of course, if you do the opposite for long enough, like GM, you may get a bailout, so maybe “profiting” isn’t a great plan. Next we’ll hear that there are oil ETFs so anyone can buy it, not just scary hedge funds.

Asked who was buying this “paper oil,” Masters told Kroft, “The California pension fund. Harvard Endowment. Lots of large institutional investors. And, by the way, other investors, hedge funds, Wall Street trading desks were following right behind them, putting money – sovereign wealth funds were putting money in the futures markets as well. So you had all these investors putting money in the futures markets. And that was driving the price up.”

So the scandal is that the rise in oil was benefiting schools and retirees. Got it.

Look, speculators don’t make an asset go up all buy itself. For any buyer, there also must be a seller. The people who bought oil were taking on the risk, and that later hurt them.If anyone had any doubts, they were dispelled a few days after that hearing when the price of oil jumped $25 in a single day. That day was Sept. 22.

Michael Greenberger, a former director of trading for the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the federal agency that oversees oil futures, says there were no supply disruptions that could have justified such a big increase.

“Did China and India suddenly have gigantic needs for new oil products in a single day? No. Everybody agrees supply-demand could not drive the price up $25, which was a record increase in the price of oil. The price of oil went from somewhere in the 60s to $147 in less than a year. And we were being told, on that run-up, ‘It’s supply-demand, supply-demand, supply-demand,'” Greenberger said.The complaint is that oil went from $60 to $147 in less than a year. But now, it’s lower than where it started. Steve doesn’t bother to mention that fact which seems pretty important to me. Hey, let’s talk with a wiped out speculator. And that $25 one-day jump came AFTER oil hit its peak. So supply and demand did work after all. What failed was the ability of Mr. Greenberger or anyone else in the government to see it coming. Seems like a good argument against regulation.

“From quarter four of ’07 until the second quarter of ’08 the EIA, the Energy Information Administration, said that supply went up, worldwide supply went up. And worldwide demand went down. So you have supply going up and demand going down, which generally means the price is going down,” Masters told Kroft.

“And this was the period of the spike,” Kroft noted.

“This was the period of the spike,” Masters agreed. “So you had the largest price increase in history during a time when actual demand was going down and actual supply was going up during the same period. However, the only thing that makes sense that lifted the price was investor demand.”So Steve, a reasonable question would be: “Did you short oil?” Or, did you ever wonder why demand was falling? The answer is simple: Higher prices were impacting demand. The system was working.

Masters believes the investor demand for commodities, and oil futures in particular, was created on Wall Street by hedge funds and the big Wall Street investment banks like Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Barclays, and J.P. Morgan, who made billions investing hundreds of billions of dollars of their clients’ money.

“The investment banks facilitated it,” Masters said. “You know, they found folks to write papers espousing the benefits of investing in commodities. And then they promoted commodities as a, quote/unquote, ‘asset class.’ Like, you could invest in commodities just like you could in stocks or bonds or anything else, like they were suitable for long-term investment.”There’s no need to use the phrase “quote/unquote.” Commodities are indeed an asset class. This is fear-mongering masquerading as “quote/unquote” journalism.

As far as suitable long-term investments go, gold has been holding its own against stocks for a couple years now. And what’s worse, I bet a lot of gold investors never take delivery either.“Are you saying that companies like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley and Barclays have as much to do with the price of oil going up as Exxon? Or…Shell?” Kroft asked.

“Yes,” Gilligan said. “I tease people sometimes that, you know, people say, ‘Well, who’s the largest oil company in America?’ And they’ll always say, ‘Well, Exxon Mobil or Chevron, or BP.’ But I’ll say, ‘No. Morgan Stanley.'”

Morgan Stanley isn’t an oil company in the traditional sense of the word – it doesn’t own or control oil wells or refineries, or gas stations. But according to documents filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Morgan Stanley is a significant player in the wholesale market through various entities controlled by the corporation.Anyone see Morgan’s stock lately? I have. I own it.

The Wall Street bank Goldman Sachs also has huge stakes in companies that own a refinery in Coffeyville, Kan., and control 43,000 miles of pipeline and more than 150 storage terminals.

And analysts at both investment banks contributed to the oil frenzy that drove prices to record highs: Goldman’s top oil analyst predicted last March that the price of a barrel was going to $200; Morgan Stanley predicted $150 a barrel.So Goldman drove up an asset that it owned. Do we know if the bank got clobbered once oil plunged?

Asked if there is price manipulation going on, Dan Gilligan told Kroft, “I can’t say. And the reason I can’t say it, is because nobody knows. Our federal regulators don’t have access to the data. They don’t know who holds what positions.”

“Why don’t they know?” Kroft asked.

“Because federal law doesn’t give them the jurisdiction to find out,” Gilligan said.So now we have our scoop. Price manipulation might be going on, but we have zero evidence of it. But now we’re going to hear that dark forces are at work.

And in 2000, Congress effectively deregulated the futures market, granting exemptions for complicated derivative investments called oil swaps, as well as electronic trading on private exchanges.

“Who was responsible for deregulating the oil future market?” Kroft asked Michael Greenberger.

“You’d have to say Enron,” he replied. “This was something they desperately wanted, and they got.”Just mention Enron and suddenly you have a story. Let’s ignore the fact that nearly every commodity was soaring.

“When Enron failed, we learned that Enron, and its conspirators who used their trading engine, were able to drive the price of electricity up, some say, by as much as 300 percent on the West Coast,” he added.

“Is the same thing going on right now in the oil business?” Kroft asked.

“Every Enron trader, who knew how to do these manipulations, became the most valuable employee on Wall Street,” Greenberger said.Again, we have zero proof of anything. Just some people made money and some people lost money. Now Kroft has to update the story to account for the gigantic decline in oil, so we now do a quick about-face.

But some of them may now be looking for work. The oil bubble began to deflate early last fall when Congress threatened new regulations and federal agencies announced they were beginning major investigations. It finally popped with the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers and the near collapse of AIG, who were both heavily invested in the oil markets. With hedge funds and investment houses facing margin calls, the speculators headed for the exits.

“From July 15th until the end of November, roughly $70 billion came out of commodities futures from these index funds,” Masters explained. “In fact, gasoline demand went down by roughly five percent over that same period of time. Yet the price of crude oil dropped more than $100 a barrel. It dropped 75 percent.”

Asked how he explains that, Masters said, “By looking at investors, that’s the only way you can explain it.”Yes, it’s the only way. Just as it is all the time.

The last sentence is the worst. I can’t believe a professional journalist said these words:The regulatory lapses in the commodities market that many believe fomented the rampant speculation in oil have still not been addressed, although the incoming Obama administration has promised to do so.

-

Citigroup Starts to Break Apart

Eddy Elfenbein, January 10th, 2009 at 3:11 pmNow that everything has blown up in their faces, Citigroup (C) is taking the first steps in breaking itself up. The WSJ reports:

Citigroup Inc., under pressure from the federal government, took a big step toward breaking up the financial supermarket, entering discussions to spin-off its Smith Barney brokerage unit into a joint venture with rival Morgan Stanley, according to people familiar with the talks.

News of the talks, which could result in an agreement as soon as next week, surfaced Friday afternoon as Robert Rubin, a senior counselor and director at Citigroup, announced his retirement from the New York company. The former Treasury secretary brought his high profile and respectability to Citigroup, but his reputation was diminished by his role in the financial turmoil at the bank.This is long, long overdue. In fact, some of us were telling them to break long before the troubles started:

The financial supermarket idea doesn’t work. Repeat after me, Mr. Prince, it doesn’t work. I know, it sounds good on paper, but people don’t do their finances that way. They never have and they’re not about to now. This was just a nice idea to justify some lousy acquisitions many, many years ago.

Eddy’s rule of business #15,783: No matter who is put in charge to execute a dumb idea, when it starts to fail, people will blame the execution, not the dumb idea. Lots of people are ready to toss Chuck Prince overboard. Fine, but he’s not the problem.

Twenty-five years ago, Sears bought Dean Witter. They had this great idea. Stick brokerage offices in the stores! Well, it didn’t work and Sears eventually sold Dean Witter. Later Dean Witter bought Discover and turned it into a hugely profitable credit card business. Then Morgan merged with Dean Witter, and made a whole lotta money.

Guess what Morgan is spinning off now? Discover!

Think about it, Chuck. Split Citi up. -

Some Madoff “Victims” Made Profits

Eddy Elfenbein, January 10th, 2009 at 11:18 amThe Securities Investor Protection Corp. has informed Madoff investors that they can apply for up to $500,000 in aid. There’s one little problem: Many of these folks made money from Madoff.

Jonathan Levitt, a New Jersey attorney who represents several former Madoff clients, said more than half of the victims who called his office looking for help have turned out to be people whose long-term profits exceeded their principal investment.

“There are a lot of net winners,” he said.

Asked for an example, Levitt said one caller, whom he declined to name, invested $1.8 million with Madoff more than a decade ago, then cashed out nearly $3 million worth of “profits” as the years went by.

On paper, he still had $4 million invested with Madoff when the scheme collapsed, but it now looks as if that figure was almost entirely comprised of fictitious profits on investments that were never actually made, leaving his claim to be owed anything unclear.Legally, this isn’t going to be pretty. The courts may rule that the recent profits have to be returned. This will pit the Madoff winners against the Madoff losers.

-

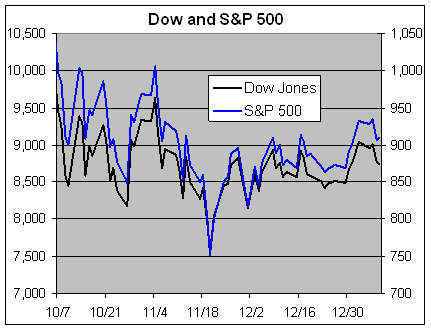

Dow and the S&P 500

Eddy Elfenbein, January 9th, 2009 at 6:36 pmOn November 20, the Dow’s ratio to the S&P 500 broke 10-to-1 for the first time in over four decades. What did that mean?

I’m not sure but it did happen to coincide with the market’s bottom. Both indexes have rallied nicely since then.

The black line is the Dow and it follows the left scale. The blue line is the S&P 500 and it follows the right scale. The lines are scaled at 10-to-1. -

Dennis Kneale Asks if Steve Jobs has PMS

Eddy Elfenbein, January 9th, 2009 at 1:44 pm

Stay classy, Dennis. -

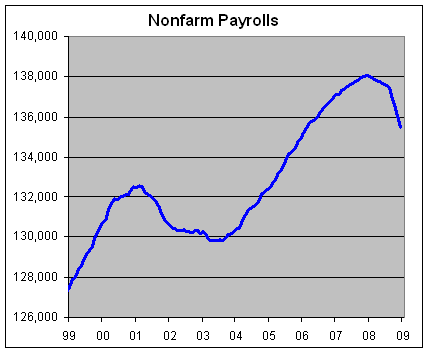

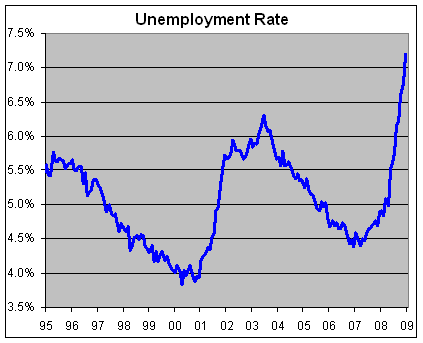

Today’s Jobs Report

Eddy Elfenbein, January 9th, 2009 at 1:23 pmThe jobs report today was terrible. The good news is that the market was expecting it, so stocks aren’t getting clobbered.

Here’s some perspective: On average, 16,000 people lost their job every day for the last four months of the year. That’s like a decent-sized town getting wiped out every day.

Here’s the NFP (in thousands):

That trend does not look good. Eleven million Americans are now unemployed. Over the last three years, the labor force has grown by 4.44 million, yet employment has grown by 555,000.

-

Daron Acemoglu

Eddy Elfenbein, January 9th, 2009 at 12:42 pmArnold Kling points to some thoughts from Daron Acemoglu on what caused our blindness:

The first is that the era of aggregate volatility had come to an end. We believed that through astute policy or new technologies, including better methods of communication and inventory control, the business cycles were conquered. Our belief in a more benign economy made us more optimistic about the stock market and the housing market. If any contraction must be soft and short lived, then it becomes easier to believe that financial intermediaries, firms and consumers should not worry about large drops in asset values.

Even though the data robustly show a negative relationship between income per capita of an economy and its volatility and many measures did show a marked decline in aggregate volatility since the 1950s, and certainly since the prewar era, these empirical patterns neither mean that the business cycles have disappeared nor that catastrophic economic events are impossible. The same economic and financial changes that have made our economy more diversified and individuals firms better insured have also increased the interconnections among them. Since the only way diversification of idiosyncratic risks can happen is by sharing these risks among many companies and individuals, better diversification also creates a multitude of counter-party relationships. Such interconnections make the economic system more robust against small shocks because new financial products successfully diversify a wide range of idiosyncratic risks and reduce business failures. But they also make the economy more vulnerable to certain low-probability, “tail” events precisely because the interconnections that are an inevitable precipitate of the greater diversification create potential domino effects among financial institutions, companies and households. In this light, perhaps we should not find it surprising that years of economic calm can be followed by tumultuous times and notable volatility.

-

-

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His