Archive for December, 2010

-

Motricity Under $20

Eddy Elfenbein, December 29th, 2010 at 2:18 pmI’ve wanted to post more this week, but honestly, nothing is happening. This market is about as dull as it can be.

I’ve had my eye on Motricity (MOTR) which is an interesting stock. It’s a bit too speculative to put on the Buy List, but it’s recently fallen under $20 per share. I think that’s a good price for more aggressive investors.

The company IPO’d in June at $10. Actually, the IPO was severely cut back. The company originally wanted a much larger offering. Still, the stock struck a chord on Wall Street and by November it was over $30 per share. Now it’s back below $20. Wall Street currently expects earnings next year of 80 cents per share.

-

Reminder: The 2011 Buy List

Eddy Elfenbein, December 29th, 2010 at 1:02 pmWith half a week to go in 2010, here again is the 2011 Buy List. The new list will take effect starting on Monday:

Abbott Laboratories (ABT)

AFLAC (AFL)

Becton, Dickinson & Co. (BDX)

Bed Bath & Beyond (BBBY)

Deluxe Corp. (DLX)

Fiserv (FISV)

Ford Motor Company (F)

Gilead Sciences (GILD)

Johnson & Johnson (JNJ)

Jos. A Bank Clothiers (JOSB)

JPMorgan Chase (JPM)

Leucadia National (LUK)

Medtronic (MDT)

Moog (MOG-A)

Nicholas Financial (NICK)

Oracle (ORCL)

Reynolds American (RAI)

Stryker (SYK)

Sysco (SYY)

Wright Express (WXS) -

Keeping Tabs on Economic Bets

Eddy Elfenbein, December 29th, 2010 at 9:48 amThirty years ago, Julian Simon and Paul Erlich made a famous bet on the direction of commodity prices. Erlich was one of those “gloom and doom” writers who said that we’re living in an age of scarcity.

Simon asked Erlich to choose any five commodities and averred that the prices would decrease over the next decade. Erlich avowed that they would increase. Erlich chose copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten. All five went down and in 1990, Erlich paid up.

Now John Tierney and Matthew R. Simmons have just settled a five-year-old $5,000 bet over whether or not oil would average $200 in 2010.

The bet was occasioned by a cover article in August 2005 in The New York Times Magazine titled “The Breaking Point.” It featured predictions of soaring oil prices from Mr. Simmons, who was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the head of a Houston investment bank specializing in the energy industry, and the author of “Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy.”

I called Mr. Simmons to discuss a bet. To his credit — and unlike some other Malthusians — he was eager to back his predictions with cash. He expected the price of oil, then about $65 a barrel, to more than triple in the next five years, even after adjusting for inflation. He offered to bet $5,000 that the average price of oil over the course of 2010 would be at least $200 a barrel in 2005 dollars.

I took him up on it, not because I knew much about Saudi oil production or the other “peak oil” arguments that global production was headed downward. I was just following a rule learned from a mentor and a friend, the economist Julian L. Simon.

As the leader of the Cornucopians, the optimists who believed there would always be abundant supplies of energy and other resources, Julian figured that betting was the best way to make his argument. Optimism, he found, didn’t make for cover stories and front-page headlines.

So how did oil prices do? At first, things were going in Mr. Simmons’ direction. Oil hit $145 per barrel by 2008. Then the recession came and oil dropped to $50. For 2010, oil has averaged $80. Adjusted for inflation that’s about $71 per barrel which isn’t too far from the $65 when the bet was made in 2005.

It’s true that the real price of oil is slightly higher now than it was in 2005, and it’s always possible that oil prices will spike again in the future. But the overall energy situation today looks a lot like a Cornucopian feast, as my colleagues Matt Wald and Cliff Krauss have recently reported. Giant new oil fields have been discovered off the coasts of Africa and Brazil. The new oil sands projects in Canada now supply more oil to the United States than Saudi Arabia does. Oil production in the United States increased last year, and the Department of Energy projects further increases over the next two decades.

The really good news is the discovery of vast quantities of natural gas. It’s now selling for less than half of what it was five years ago. There’s so much available that the Energy Department is predicting low prices for gas and electricity for the next quarter-century. Lobbyists for wind farms, once again, have been telling Washington that the “sustainable energy” industry can’t sustain itself without further subsidies.

As gas replaces dirtier fossil fuels, the rise in greenhouse gas emissions will be tempered, according to the Department of Energy. It projects that no new coal power plants will be built, and that the level of carbon dioxide emissions in the United States will remain below the rate of 2005 for the next 15 years even if no new restrictions are imposed.

Maybe something unexpected will change these happy trends, but for now I’d say that Julian Simon’s advice remains as good as ever. You can always make news with doomsday predictions, but you can usually make money betting against them.

In April 2008, Prieur du Plessis and Barry Ritholtz highlighted a $1 million bet from Jim Sinclair that gold would hit $1,650 per ounce by the second week of January 2011.

I don’t know if anyone took him up on his offer. There are only a few days left and unless gold stages a big rally, it looks like Sinclair will have lost.

-

Morning News: December 29, 2010

Eddy Elfenbein, December 29th, 2010 at 7:45 amIn the Rearview, a Year That Fizzled

Sweden Shows Central Bankers How to Fight Next Asset Bubble

Consumer Confidence Dips on Worries

Oil Steadies Above $91 Ahead of U.S. Inventory Data

Copper Climbs to Record in London on Speculation of More Growth

Washington Region Posts Gains as Home Prices Still Falling in Most U.S. Cities

Derivatives Clearing Group Decides Against Registration

Hot Trade in Private Shares of Facebook

Groupon Files for $950 Million Equity Financing Round

GM Stock Hits $35.32 Per Share

The Shanghai Divergence (a Low-Probability Bet on Repatriation)

-

Snore!

Eddy Elfenbein, December 28th, 2010 at 11:26 amOMG, this is a dull trading day. Dull, dull, dull.

Of the 100 stocks in the S&P 100, 91 are up or down less than 0.9%.

Only nine are up or down by more than 1%. Not one currently has a swing of more than 1.5%.

-

Happy 100th Birthday Ronald Coase

Eddy Elfenbein, December 28th, 2010 at 10:11 amHere are some questions to ponder: Why are there are companies? Why doesn’t everyone work for themselves as independent contractors? Why is it necessary for people to congregate into companies, some small and some very large?

In 1937, Ronald Coase had an answer:

His central insight was that firms exist because going to the market all the time can impose heavy transaction costs. You need to hire workers, negotiate prices and enforce contracts, to name but three time-consuming activities. A firm is essentially a device for creating long-term contracts when short-term contracts are too bothersome. But if markets are so inefficient, why don’t firms go on getting bigger for ever? Mr Coase also pointed out that these little planned societies impose transaction costs of their own, which tend to rise as they grow bigger. The proper balance between hierarchies and markets is constantly recalibrated by the forces of competition: entrepreneurs may choose to lower transaction costs by forming firms but giant firms eventually become sluggish and uncompetitive.

Dr. Coase turns 100 tomorrow. He’s also said that he’s been working on his next book.

Here’s a lecture he gave at the University of Chicago Law School in 2003:

-

Ugly Case Shiller Report

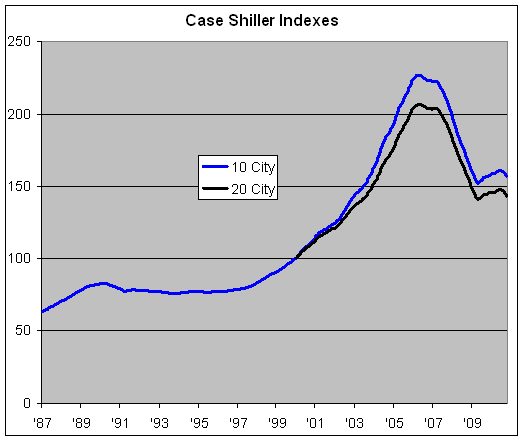

Eddy Elfenbein, December 28th, 2010 at 9:46 amThere’s still not much strength in housing. Today’s Case Shiller report showed that home prices actually fell last month.

The Case Shiller Index tracks a 20-city index and a 10-city index. Both indexes peaked in April 2006 and hit bottom in May 2009. Both indexes dropped by roughly one-third over that 37-month period.

The year-to-year increases were seen in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco and Washington. While composite prices remain above their spring 2009 lows, six markets hit their lowest levels since home prices began dropping in 2006 and 2007: Atlanta, Charlotte, N.C., Portland, Ore., Miami, Seattle and Tampa, Fla.

David Blitzer, chairman of S&P’s index committee, said “The double-dip is almost here, as six cities set new lows for the period since the 2006 peaks. There is no good news in October’s report. Home prices across the country continue to fall.”

The indexes, based on the three-month averages of home prices, turned lower in August for the first time in four months, a delayed response to the housing-market weakness after federal home-buyer tax credits expired in April. Prices declined again in September, with the rate of decline showing signs of accelerating.

However, recent data show home sales are recovering a bit despite high unemployment, a sluggish economy and worries about flaws in foreclosure documents. The National Association of Realtors said last week that sales of previously occupied homes increased a less-than-expected 5.6% in November after falling 2.2% in October. Prices for existing homes edged up for the first time since August, rising 0.4% from a year earlier but little changed from October.

The Case-Shiller index of 10 major metropolitan areas declined 1.2% from September, while the 20-city index fell 1.3%. However, they were up 0.2% and down 0.8%, respectively, from a year earlier. Adjusted for seasonal factors, the sequential declines were 0.9% and 1%, respectively.

In October, prices in every metropolitan statistical area covered by the index fell from September. Month-to-month decliners were led by Atlanta and Detroit, which were down 2.9% and 2.5%, respectively.

-

Morning News: December 28, 2010

Eddy Elfenbein, December 28th, 2010 at 8:06 amFed Bond Buys Unlikely to Top $600 Billion

Dollar Weakens a Fourth Day Before U.S. Home Data; Franc Rises

Retail Sales Rebound, Beating Forecasts

China Cuts First-Round Rare Earth Export Quotas by 11%

Bailed-Out Banks Remain in Danger of Failing: 98 Banks at Risk

Gold Rises in New York as Dollar’s Drop Boosts Investor Demand

Housing Starts Seen Rising to 3-Year High With Boost for Jobs

AIG Gets $4.3 Billion of Credit as Insurer Sees Bailout Exit `Finish Line’

Alcatel to Pay $137 Million to Settle Bribery Charges

Dai-ichi to Take Over Australia’s Tower for $1.2 Billion

-

The S&P 500’s Price/Earnings Ratio

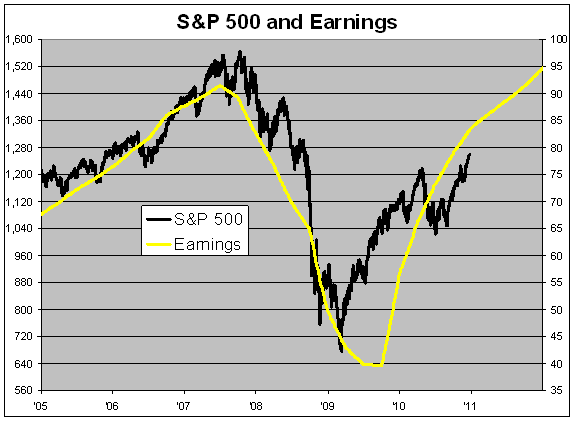

Eddy Elfenbein, December 27th, 2010 at 1:54 pmAlthough the market has had a strong run over the past 21 months, the S&P 500 doesn’t appear to be overpriced according to the market’s P/E Ratio.

For 2008, the market earned just $48.51. Last year, earnings climbed to $56.86. This year, earnings are projected to be $83.68. Earnings for next year are projected to be $94.76.

Here’s a look at the S&P 500 (black line, left scale) along with its trailing operating earnings (gold line, right scale). The two lines are scaled at a ratio of 16 to 1 which means that when the lines cross, the P/E Ratio is exactly 16.

-

The New Normal

Eddy Elfenbein, December 27th, 2010 at 11:14 amIn the NYT, Paul Lim explains why investor optimism may be a red flag:

It’s worth remembering that even though a strong year-end surge has pushed the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index up 20 percent since the start of September, it’s just part of a tremendous rally over the past two years.

Since the bull market began in March 2009, the S.& P. 500 has climbed more than 86 percent. And investments that are considered riskier than blue-chip domestic stocks — such as emerging-market equities or shares of fast-growing but volatile small companies — have done even better during this stretch. Both the Russell 2000 small-stock index and the Morgan Stanley Capital International Emerging Market index have gained 130 percent.

“We were told that this was supposed to be a ‘new normal’ era where investors should expect lower returns and shouldn’t take much risk as a result,” says James W. Paulsen, chief investment strategist at Wells Capital Management. “But the performance of risk assets over the past 18 months shows that this was anything but a new normal.”

Risk-taking hasn’t been rewarded over just the last 18 months. Despite all the talk about what a “lost decade” this has been for investors, risky asset classes have actually produced sizable gains over the last 10 years. For instance, though the average fund that invests in large-capitalization domestic stocks gained just 1.5 percent, annualized, in that period, small-stock funds returned nearly 7 percent a year. And emerging-market stock funds returned nearly 15 percent, annualized, during that stretch, according to Morningstar.

Risk-taking was also well rewarded in the fixed-income markets. While safe government bond funds gained 4.8 percent, on average, for the past decade, slightly riskier investment-grade corporate bond funds gained 5.4 percent, annualized, and high-yield bond funds — even riskier — returned nearly 7 percent a year.

In general, the more risk you took in asset allocation, the greater your relative performance over the past decade, says Jeffrey N. Kleintop, chief market strategist at LPL Financial.

But that can’t go on forever. Sam Stovall, chief investment strategist at S.& P., looked at how bull markets have unfolded historically since 1949. He found that while the S.& P. has soared 35 percent, on average, in the first 12 months of a new rally, those gains have slowed to an average of 17 percent in the second year of a bull market and just 5 percent in the third year.

-

-

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His