Archive for August, 2012

-

The Buy List So Far

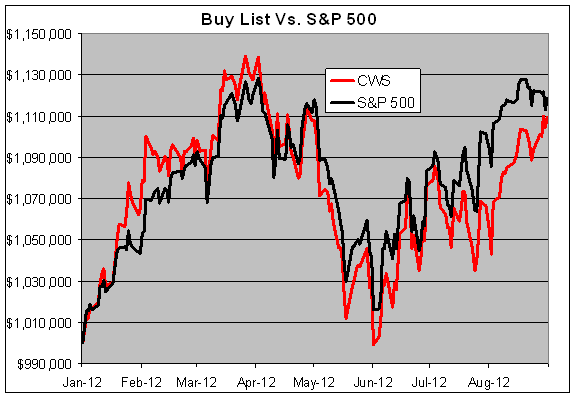

Eddy Elfenbein, August 31st, 2012 at 10:48 pmThe year is now officially two-thirds over, so let’s look at how our Buy List is doing so far.

Our set-and-forget Buy List has outperformed the S&P 500 for the last five years in a row, but this year looks like it’s going to be a tough battle. I think it may come down to the last few days.

Through today, August 31st, our Buy List is up 10.92% (not including dividends). That’s a pretty decent return for eight months. The S&P 500 is up 11.85%, so we’re trailing the market by just 93 basis points. That’s very close.

My goal with the Buy List is to show investors that you can beat the market by using a conservative low-turnover (some might say lazy) strategy. It can be done and we’ve done it.

Our deficit is quite small and another week like last week could easily vault us ahead of the market. Best of all, we haven’t made one single change all year. Zero commissions. In fact, if JPM was back at $44 like it was pre-Whale, then we’d be ahead of the market. I’m confident we can regain the lead before the year is over.

-

Bernanke in Jackson Hole

Eddy Elfenbein, August 31st, 2012 at 12:31 pmHere’s a transcript of today’s big speech in Jackson Hole:

Monetary Policy since the Onset of the Crisis

When we convened in Jackson Hole in August 2007, the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) target for the federal funds rate was 5-1/4 percent. Sixteen months later, with the financial crisis in full swing, the FOMC had lowered the target for the federal funds rate to nearly zero, thereby entering the unfamiliar territory of having to conduct monetary policy with the policy interest rate at its effective lower bound. The unusual severity of the recession and ongoing strains in financial markets made the challenges facing monetary policymakers all the greater.

Today I will review the evolution of U.S. monetary policy since late 2007. My focus will be the Federal Reserve’s experience with nontraditional policy tools, notably those based on the management of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and on its public communications. I’ll discuss what we have learned about the efficacy and drawbacks of these less familiar forms of monetary policy, and I’ll talk about the implications for the Federal Reserve’s ongoing efforts to promote a return to maximum employment in a context of price stability.

Monetary Policy in 2007 and 2008

When significant financial stresses first emerged, in August 2007, the FOMC responded quickly, first through liquidity actions–cutting the discount rate and extending term loans to banks–and then, in September, by lowering the target for the federal funds rate by 50 basis points. As further indications of economic weakness appeared over subsequent months, the Committee reduced its target for the federal funds rate by a cumulative 325 basis points, leaving the target at 2 percent by the spring of 2008.The Committee held rates constant over the summer as it monitored economic and financial conditions. When the crisis intensified markedly in the fall, the Committee responded by cutting the target for the federal funds rate by 100 basis points in October, with half of this easing coming as part of an unprecedented coordinated interest rate cut by six major central banks. Then, in December 2008, as evidence of a dramatic slowdown mounted, the Committee reduced its target to a range of 0 to 25 basis points, effectively its lower bound. That target range remains in place today.

Despite the easing of monetary policy, dysfunction in credit markets continued to worsen. As you know, in the latter part of 2008 and early 2009, the Federal Reserve took extraordinary steps to provide liquidity and support credit market functioning, including the establishment of a number of emergency lending facilities and the creation or extension of currency swap agreements with 14 central banks around the world. In its role as banking regulator, the Federal Reserve also led stress tests of the largest U.S. bank holding companies, setting the stage for the companies to raise capital. These actions–along with a host of interventions by other policymakers in the United States and throughout the world–helped stabilize global financial markets, which in turn served to check the deterioration in the real economy and the emergence of deflationary pressures.

Unfortunately, although it is likely that even worse outcomes had been averted, the damage to the economy was severe. The unemployment rate in the United States rose from about 6 percent in September 2008 to nearly 9 percent by April 2009–it would peak at 10 percent in October–while inflation declined sharply. As the crisis crested, and with the federal funds rate at its effective lower bound, the FOMC turned to nontraditional policy approaches to support the recovery.

As the Committee embarked on this path, we were guided by some general principles and some insightful academic work but–with the important exception of the Japanese case–limited historical experience. As a result, central bankers in the United States, and those in other advanced economies facing similar problems, have been in the process of learning by doing. I will discuss some of what we have learned, beginning with our experience conducting policy using the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, then turn to our use of communications tools.

Balance Sheet Tools

In using the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet as a tool for achieving its mandated objectives of maximum employment and price stability, the FOMC has focused on the acquisition of longer-term securities–specifically, Treasury and agency securities, which are the principal types of securities that the Federal Reserve is permitted to buy under the Federal Reserve Act. One mechanism through which such purchases are believed to affect the economy is the so-called portfolio balance channel, which is based on the ideas of a number of well-known monetary economists, including James Tobin, Milton Friedman, Franco Modigliani, Karl Brunner, and Allan Meltzer. The key premise underlying this channel is that, for a variety of reasons, different classes of financial assets are not perfect substitutes in investors’ portfolios. For example, some institutional investors face regulatory restrictions on the types of securities they can hold, retail investors may be reluctant to hold certain types of assets because of high transactions or information costs, and some assets have risk characteristics that are difficult or costly to hedge.Imperfect substitutability of assets implies that changes in the supplies of various assets available to private investors may affect the prices and yields of those assets. Thus, Federal Reserve purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), for example, should raise the prices and lower the yields of those securities; moreover, as investors rebalance their portfolios by replacing the MBS sold to the Federal Reserve with other assets, the prices of the assets they buy should rise and their yields decline as well. Declining yields and rising asset prices ease overall financial conditions and stimulate economic activity through channels similar to those for conventional monetary policy. Following this logic, Tobin suggested that purchases of longer-term securities by the Federal Reserve during the Great Depression could have helped the U.S. economy recover despite the fact that short-term rates were close to zero, and Friedman argued for large-scale purchases of long-term bonds by the Bank of Japan to help overcome Japan’s deflationary trap.

Large-scale asset purchases can influence financial conditions and the broader economy through other channels as well. For instance, they can signal that the central bank intends to pursue a persistently more accommodative policy stance than previously thought, thereby lowering investors’ expectations for the future path of the federal funds rate and putting additional downward pressure on long-term interest rates, particularly in real terms. Such signaling can also increase household and business confidence by helping to diminish concerns about “tail” risks such as deflation. During stressful periods, asset purchases may also improve the functioning of financial markets, thereby easing credit conditions in some sectors.

With the space for further cuts in the target for the federal funds rate increasingly limited, in late 2008 the Federal Reserve initiated a series of large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs). In November, the FOMC announced a program to purchase a total of $600 billion in agency MBS and agency debt. In March 2009, the FOMC expanded this purchase program substantially, announcing that it would purchase up to $1.25 trillion of agency MBS, up to $200 billion of agency debt, and up to $300 billion of longer-term Treasury debt. These purchases were completed, with minor adjustments, in early 2010. In November 2010, the FOMC announced that it would further expand the Federal Reserve’s security holdings by purchasing an additional $600 billion of longer-term Treasury securities over a period ending in mid-2011.

About a year ago, the FOMC introduced a variation on its earlier purchase programs, known as the maturity extension program (MEP), under which the Federal Reserve would purchase $400 billion of long-term Treasury securities and sell an equivalent amount of shorter-term Treasury securities over the period ending in June 2012. The FOMC subsequently extended the MEP through the end of this year. By reducing the average maturity of the securities held by the public, the MEP puts additional downward pressure on longer-term interest rates and further eases overall financial conditions.

How effective are balance sheet policies? After nearly four years of experience with large-scale asset purchases, a substantial body of empirical work on their effects has emerged. Generally, this research finds that the Federal Reserve’s large-scale purchases have significantly lowered long-term Treasury yields. For example, studies have found that the $1.7 trillion in purchases of Treasury and agency securities under the first LSAP program reduced the yield on 10-year Treasury securities by between 40 and 110 basis points. The $600 billion in Treasury purchases under the second LSAP program has been credited with lowering 10-year yields by an additional 15 to 45 basis points. Three studies considering the cumulative influence of all the Federal Reserve’s asset purchases, including those made under the MEP, found total effects between 80 and 120 basis points on the 10-year Treasury yield. These effects are economically meaningful.

Importantly, the effects of LSAPs do not appear to be confined to longer-term Treasury yields. Notably, LSAPs have been found to be associated with significant declines in the yields on both corporate bonds and MBS. The first purchase program, in particular, has been linked to substantial reductions in MBS yields and retail mortgage rates. LSAPs also appear to have boosted stock prices, presumably both by lowering discount rates and by improving the economic outlook; it is probably not a coincidence that the sustained recovery in U.S. equity prices began in March 2009, shortly after the FOMC’s decision to greatly expand securities purchases. This effect is potentially important because stock values affect both consumption and investment decisions.

While there is substantial evidence that the Federal Reserve’s asset purchases have lowered longer-term yields and eased broader financial conditions, obtaining precise estimates of the effects of these operations on the broader economy is inherently difficult, as the counterfactual–how the economy would have performed in the absence of the Federal Reserve’s actions–cannot be directly observed. If we are willing to take as a working assumption that the effects of easier financial conditions on the economy are similar to those observed historically, then econometric models can be used to estimate the effects of LSAPs on the economy. Model simulations conducted at the Federal Reserve generally find that the securities purchase programs have provided significant help for the economy. For example, a study using the Board’s FRB/US model of the economy found that, as of 2012, the first two rounds of LSAPs may have raised the level of output by almost 3 percent and increased private payroll employment by more than 2 million jobs, relative to what otherwise would have occurred. The Bank of England has used LSAPs in a manner similar to that of the Federal Reserve, so it is of interest that researchers have found the financial and macroeconomic effects of the British programs to be qualitatively similar to those in the United States.

To be sure, these estimates of the macroeconomic effects of LSAPs should be treated with caution. It is likely that the crisis and the recession have attenuated some of the normal transmission channels of monetary policy relative to what is assumed in the models; for example, restrictive mortgage underwriting standards have reduced the effects of lower mortgage rates. Further, the estimated macroeconomic effects depend on uncertain estimates of the persistence of the effects of LSAPs on financial conditions. Overall, however, a balanced reading of the evidence supports the conclusion that central bank securities purchases have provided meaningful support to the economic recovery while mitigating deflationary risks.

Now I will turn to our use of communications tools.

Communication Tools

Clear communication is always important in central banking, but it can be especially important when economic conditions call for further policy stimulus but the policy rate is already at its effective lower bound. In particular, forward guidance that lowers private-sector expectations regarding future short-term rates should cause longer-term interest rates to decline, leading to more accommodative financial conditions.The Federal Reserve has made considerable use of forward guidance as a policy tool. From March 2009 through June 2011, the FOMC’s postmeeting statement noted that economic conditions “are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an extended period.” At the August 2011 meeting, the Committee made its guidance more precise by stating that economic conditions would likely warrant that the federal funds rate remain exceptionally low “at least through mid-2013.” At the beginning of this year, the FOMC extended the anticipated period of exceptionally low rates further, to “at least through late 2014,” guidance that has been reaffirmed at subsequent meetings. As the language indicates, this guidance is not an unconditional promise; rather, it is a statement about the FOMC’s collective judgment regarding the path of policy that is likely to prove appropriate, given the Committee’s objectives and its outlook for the economy.

The views of Committee members regarding the likely timing of policy firming represent a balance of many factors, but the current forward guidance is broadly consistent with prescriptions coming from a range of standard benchmarks, including simple policy rules and optimal control methods. Some of the policy rules informing the forward guidance relate policy interest rates to familiar determinants, such as inflation and the output gap. But a number of considerations also argue for planning to keep rates low for a longer time than implied by policy rules developed during more normal periods. These considerations include the need to take out insurance against the realization of downside risks, which are particularly difficult to manage when rates are close to their effective lower bound; the possibility that, because of various unusual headwinds slowing the recovery, the economy needs more policy support than usual at this stage of the cycle; and the need to compensate for limits to policy accommodation resulting from the lower bound on rates.

Has the forward guidance been effective? It is certainly true that, over time, both investors and private forecasters have pushed out considerably the date at which they expect the federal funds rate to begin to rise; moreover, current policy expectations appear to align well with the FOMC’s forward guidance. To be sure, the changes over time in when the private sector expects the federal funds rate to begin firming resulted in part from the same deterioration of the economic outlook that led the FOMC to introduce and then extend its forward guidance. But the private sector’s revised outlook for the policy rate also appears to reflect a growing appreciation of how forceful the FOMC intends to be in supporting a sustainable recovery. For example, since 2009, forecasters participating in the Blue Chip survey have repeatedly marked down their projections of the unemployment rate they expect to prevail at the time that the FOMC begins to lift the target for the federal funds rate away from zero. Thus, the Committee’s forward guidance may have conveyed a greater willingness to maintain accommodation than private forecasters had previously believed. The behavior of financial market prices in periods around changes in the forward guidance is also consistent with the view that the guidance has affected policy expectations.

Making Policy with Nontraditional Tools: A Cost-Benefit Framework

Making monetary policy with nontraditional tools is challenging. In particular, our experience with these tools remains limited. In this context, the FOMC carefully compares the expected benefits and costs of proposed policy actions.The potential benefit of policy action, of course, is the possibility of better economic outcomes–outcomes more consistent with the FOMC’s dual mandate. In light of the evidence I discussed, it appears reasonable to conclude that nontraditional policy tools have been and can continue to be effective in providing financial accommodation, though we are less certain about the magnitude and persistence of these effects than we are about those of more-traditional policies.

The possible benefits of an action, however, must be considered alongside its potential costs. I will focus now on the potential costs of LSAPs.

One possible cost of conducting additional LSAPs is that these operations could impair the functioning of securities markets. As I noted, the Federal Reserve is limited by law mainly to the purchase of Treasury and agency securities; the supply of those securities is large but finite, and not all of the supply is actively traded. Conceivably, if the Federal Reserve became too dominant a buyer in certain segments of these markets, trading among private agents could dry up, degrading liquidity and price discovery. As the global financial system depends on deep and liquid markets for U.S. Treasury securities, significant impairment of those markets would be costly, and, in particular, could impede the transmission of monetary policy. For example, market disruptions could lead to higher liquidity premiums on Treasury securities, which would run counter to the policy goal of reducing Treasury yields. However, although market capacity could ultimately become an issue, to this point we have seen few if any problems in the markets for Treasury or agency securities, private-sector holdings of securities remain large, and trading among private market participants remains robust.

A second potential cost of additional securities purchases is that substantial further expansions of the balance sheet could reduce public confidence in the Fed’s ability to exit smoothly from its accommodative policies at the appropriate time. Even if unjustified, such a reduction in confidence might increase the risk of a costly unanchoring of inflation expectations, leading in turn to financial and economic instability. It is noteworthy, however, that the expansion of the balance sheet to date has not materially affected inflation expectations, likely in part because of the great emphasis the Federal Reserve has placed on developing tools to ensure that we can normalize monetary policy when appropriate, even if our securities holdings remain large. In particular, the FOMC will be able to put upward pressure on short-term interest rates by raising the interest rate it pays banks for reserves they hold at the Fed. Upward pressure on rates can also be achieved by using reserve-draining tools or by selling securities from the Federal Reserve’s portfolio, thus reversing the effects achieved by LSAPs. The FOMC has spent considerable effort planning and testing our exit strategy and will act decisively to execute it at the appropriate time.

A third cost to be weighed is that of risks to financial stability. For example, some observers have raised concerns that, by driving longer-term yields lower, nontraditional policies could induce an imprudent reach for yield by some investors and thereby threaten financial stability. Of course, one objective of both traditional and nontraditional policy during recoveries is to promote a return to productive risk-taking; as always, the goal is to strike the appropriate balance. Moreover, a stronger recovery is itself clearly helpful for financial stability. In assessing this risk, it is important to note that the Federal Reserve, both on its own and in collaboration with other members of the Financial Stability Oversight Council, has substantially expanded its monitoring of the financial system and modified its supervisory approach to take a more systemic perspective. We have seen little evidence thus far of unsafe buildups of risk or leverage, but we will continue both our careful oversight and the implementation of financial regulatory reforms aimed at reducing systemic risk.

A fourth potential cost of balance sheet policies is the possibility that the Federal Reserve could incur financial losses should interest rates rise to an unexpected extent. Extensive analyses suggest that, from a purely fiscal perspective, the odds are strong that the Fed’s asset purchases will make money for the taxpayers, reducing the federal deficit and debt. And, of course, to the extent that monetary policy helps strengthen the economy and raise incomes, the benefits for the U.S. fiscal position would be substantial. In any case, this purely fiscal perspective is too narrow: Because Americans are workers and consumers as well as taxpayers, monetary policy can achieve the most for the country by focusing generally on improving economic performance rather than narrowly on possible gains or losses on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

In sum, both the benefits and costs of nontraditional monetary policies are uncertain; in all likelihood, they will also vary over time, depending on factors such as the state of the economy and financial markets and the extent of prior Federal Reserve asset purchases. Moreover, nontraditional policies have potential costs that may be less relevant for traditional policies. For these reasons, the hurdle for using nontraditional policies should be higher than for traditional policies. At the same time, the costs of nontraditional policies, when considered carefully, appear manageable, implying that we should not rule out the further use of such policies if economic conditions warrant.

Economic Prospects

The accommodative monetary policies I have reviewed today, both traditional and nontraditional, have provided important support to the economic recovery while helping to maintain price stability. As of July, the unemployment rate had fallen to 8.3 percent from its cyclical peak of 10 percent and payrolls had risen by 4 million jobs from their low point. And despite periodic concerns about deflation risks, on the one hand, and repeated warnings that excessive policy accommodation would ignite inflation, on the other hand, inflation (except for temporary deviations caused primarily by swings in commodity prices) has remained near the Committee’s 2 percent objective and inflation expectations have remained stable. Key sectors such as manufacturing, housing, and international trade have strengthened, firms’ investment in equipment and software has rebounded, and conditions in financial and credit markets have improved.Notwithstanding these positive signs, the economic situation is obviously far from satisfactory. The unemployment rate remains more than 2 percentage points above what most FOMC participants see as its longer-run normal value, and other indicators–such as the labor force participation rate and the number of people working part time for economic reasons–confirm that labor force utilization remains at very low levels. Further, the rate of improvement in the labor market has been painfully slow. I have noted on other occasions that the declines in unemployment we have seen would likely continue only if economic growth picked up to a rate above its longer-term trend. In fact, growth in recent quarters has been tepid, and so, not surprisingly, we have seen no net improvement in the unemployment rate since January. Unless the economy begins to grow more quickly than it has recently, the unemployment rate is likely to remain far above levels consistent with maximum employment for some time.

In light of the policy actions the FOMC has taken to date, as well as the economy’s natural recovery mechanisms, we might have hoped for greater progress by now in returning to maximum employment. Some have taken the lack of progress as evidence that the financial crisis caused structural damage to the economy, rendering the current levels of unemployment impervious to additional monetary accommodation. The literature on this issue is extensive, and I cannot fully review it today. However, following every previous U.S. recession since World War II, the unemployment rate has returned close to its pre-recession level, and, although the recent recession was unusually deep, I see little evidence of substantial structural change in recent years.

Rather than attributing the slow recovery to longer-term structural factors, I see growth being held back currently by a number of headwinds. First, although the housing sector has shown signs of improvement, housing activity remains at low levels and is contributing much less to the recovery than would normally be expected at this stage of the cycle.

Second, fiscal policy, at both the federal and state and local levels, has become an important headwind for the pace of economic growth. Notwithstanding some recent improvement in tax revenues, state and local governments still face tight budget situations and continue to cut real spending and employment. Real purchases are also declining at the federal level. Uncertainties about fiscal policy, notably about the resolution of the so-called fiscal cliff and the lifting of the debt ceiling, are probably also restraining activity, although the magnitudes of these effects are hard to judge. It is critical that fiscal policymakers put in place a credible plan that sets the federal budget on a sustainable trajectory in the medium and longer runs. However, policymakers should take care to avoid a sharp near-term fiscal contraction that could endanger the recovery.

Third, stresses in credit and financial markets continue to restrain the economy. Earlier in the recovery, limited credit availability was an important factor holding back growth, and tight borrowing conditions for some potential homebuyers and small businesses remain a problem today. More recently, however, a major source of financial strains has been uncertainty about developments in Europe. These strains are most problematic for the Europeans, of course, but through global trade and financial linkages, the effects of the European situation on the U.S. economy are significant as well. Some recent policy proposals in Europe have been quite constructive, in my view, and I urge our European colleagues to press ahead with policy initiatives to resolve the crisis.

Conclusion

Early in my tenure as a member of the Board of Governors, I gave a speech that considered options for monetary policy when the short-term policy interest rate is close to its effective lower bound. I was reacting to common assertions at the time that monetary policymakers would be “out of ammunition” as the federal funds rate came closer to zero. I argued that, to the contrary, policy could still be effective near the lower bound. Now, with several years of experience with nontraditional policies both in the United States and in other advanced economies, we know more about how such policies work. It seems clear, based on this experience, that such policies can be effective, and that, in their absence, the 2007-09 recession would have been deeper and the current recovery would have been slower than has actually occurred.As I have discussed today, it is also true that nontraditional policies are relatively more difficult to apply, at least given the present state of our knowledge. Estimates of the effects of nontraditional policies on economic activity and inflation are uncertain, and the use of nontraditional policies involves costs beyond those generally associated with more-standard policies. Consequently, the bar for the use of nontraditional policies is higher than for traditional policies. In addition, in the present context, nontraditional policies share the limitations of monetary policy more generally: Monetary policy cannot achieve by itself what a broader and more balanced set of economic policies might achieve; in particular, it cannot neutralize the fiscal and financial risks that the country faces. It certainly cannot fine-tune economic outcomes.

As we assess the benefits and costs of alternative policy approaches, though, we must not lose sight of the daunting economic challenges that confront our nation. The stagnation of the labor market in particular is a grave concern not only because of the enormous suffering and waste of human talent it entails, but also because persistently high levels of unemployment will wreak structural damage on our economy that could last for many years.

Over the past five years, the Federal Reserve has acted to support economic growth and foster job creation, and it is important to achieve further progress, particularly in the labor market. Taking due account of the uncertainties and limits of its policy tools, the Federal Reserve will provide additional policy accommodation as needed to promote a stronger economic recovery and sustained improvement in labor market conditions in a context of price stability.

-

CWS Market Review – August 31, 2012

Eddy Elfenbein, August 31st, 2012 at 8:02 am“The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.” – Benjamin Graham

Even though the stock market is still in its late-summer doldrums, our Buy List stocks made some very impressive headlines this week. First, Hudson City ($HCBK) jumped 15% in one day after it announced a $3.7 billion merger agreement with M&T Bank ($MTB). Then JoS. A. Bank Clothiers ($JOSB) soared 14% thanks to a very strong earnings report. Looking at the numbers, our Buy List has had a very good August. In the last four weeks, the Buy List gained 5.9%, which is more than double the gains of the S&P 500.

As Churchill said on V-E Day, “We may allow ourselves a brief period of rejoicing.” While this month was great for our Buy List, let’s not get overconfident. This is a tough market, and there are many stocks, such as Amazon.com ($AMZN), that are extremely dangerous to own. The bond market looks shaky as well. As always, patience and discipline are our keys to success.

In this week’s CWS Market Review, I’ll bring you up to speed on the latest developments. Plus, I’ll tell you the best way to position yourself in the weeks ahead. We also had a pleasant 12.1% dividend increase from Harris Corp. ($HRS). This quiet little stock just had a remarkable run, rallying on 18 out of 21 days—and it’s still going for less than 10 times earnings. Now let’s take a closer look at the news from Hudson City and Joey Bank.

Hudson City Agrees to Merge with M&T

At the start of the week, Hudson City Bancorp said it had agreed to merge with M&T Bank ($MTB) in a deal worth $3.7 billion. Shares of HCBK jumped 15.7% on Monday.

I have to confess some embarrassment, since I had actually been down on HCBK and recently lowered the stock to a “hold.” The board members at M&T apparently aren’t subscribers to CWS Market Review. The merger between MTB and HCBK is interesting for several reasons. One is that this is the largest bank merger since Dodd-Frank came into effect. I think banks have been understandably reluctant to do any large deals since the financial crisis. Regulators certainly will be paying extra-close attention to any merger.

The merger agreement allows shareholders of Hudson City to take cash or 0.08403 shares of MTB for each share of HCBK they own. Given where MTB closed last Friday, that values HCBK at $7.22 per share. Here’s another interesting twist. The acquisitor in any large deal normally sees its stock drop. But this time, shares of MTB rallied 4.6% on Monday. That really caught Wall Street’s attention. Plus, when MTB rises, it values HCBK even more. M&T closed the day on Thursday at $87 per share, which translates to $7.31 for HCBK (note that HCBK is slightly discounted relative to the merger ratio). If MTB can get to $95, which is a very fair valuation (12.4 times next year’s earnings estimate), then that would value HCBK just shy of $8. I’m not saying it will happen, but it’s a very plausible scenario.

The merger agreement calls for the total payment from MTB to be 60% in stock and 40% in cash, so individual shareholders may not get the exact allocation they want. It all depends on what the balance of HCBK shareholders say (here’s a transcript of the conference call).

My recommendation for HCBK holders is to take shares of MTB. That’s what we’re going to do on the Buy List. M&T is a good bank, and it pays a decent dividend. M&T hasn’t had a losing quarter in 36 years. They were also one of the very few large banks to maintain their dividend through the financial crisis.

Bear in mind that we’re not in any hurry to exchange our shares. According to the conference call, the banks are looking to wrap up the deal by the second quarter of next year. That’s between seven and ten months away. I should remind you that any deal, no matter how solid it looks, does have a chance of falling apart. It’s certainly not likely, but the odds aren’t zero either. On the conference call, management said they hope to maintain Hudson’s dividend, but they need to hear from the regulators. For now, I rate Hudson City a good buy any time the shares are below $7.50.

Joey Bank Soars on Strong Earnings

On Wednesday, JoS. A. Bank Clothiers stunned everybody, including me, by reporting very strong earnings. The stock vaulted 14% that day, which came on the heels of a 3.5% rally on Tuesday. If you recall from last week’s CWS Market Review, I was rather skeptical of this earnings report.

For JOSB’s fiscal second quarter, they earned 83 cents per share, which was 10 cents more than Wall Street’s consensus. At one point on Wednesday, JOSB was up close to 19%. If you recall, the last earnings report was a dud. While the recent rally is impressive, JOSB is really taking back a lot of the ground it lost during the spring. It appears that short-sellers were ganging up on JOSB, and once the strong earnings came out, they got routed. The shorts then had to cover their positions and that drove the stock even higher, which in turn caused more shorts to scramble for the exits. That’s not a fun game to play.

Looking at the numbers in the earnings report, JOSB did quite well. Total sales rose by 12.9% to $260.3 million. That was almost $10 million more than Wall Street had been expecting. Sales at JOSB’s direct marketing segment, which includes internet sales, rose over 39%. The important metric in retailing, same-store sales, saw an impressive rise of 6.1%.

I was pleased to hear that JoS. A. Bank has very ambitious plans for the future. The company hopes to open 45 to 50 stores this fiscal year and next year as well. I’m going to raise my buy price on JOSB to $50. I also want to warn you to expect a bit of volatility from this stock. If that unnerves you, it may be best to stay away.

Harris Corp. Is a Buy up to $50

One of the biggest surprises this year has been the performance of Harris Corp. ($HRS). The company, which makes communication equipment, was a new addition to this year’s Buy List, but I don’t think I could have imagined that it would be our best-performing stock so far this year. Through Thursday’s trading, Harris is up 30.7% since the start of the year for us.

On Wednesday, Harris announced that it’s raising its quarterly dividend by 12.1%. This is their second dividend increase this year. Six months ago, Harris raised its dividend from 28 cents to 33 cents per share. Now it’s rising to 37 cents per share. That makes the current yield 3.1%, which is more than a 30-year Treasury.

Some Buy-List Bargains

As I said last week, I’m expecting a minor pullback over the next few weeks. Nothing big, but we may shed a few points here and there. In fact, the S&P 500 closed just below 1,400 on Thursday. There are good buys out there. I want to highlight a few stocks on our Buy List that look especially good right now.

Oracle’s ($ORCL) earnings, for example, are only a few weeks away. I’m expecting more good news. Ford ($F) and Moog ($MOG-A) are pretty cheap here. If volatility doesn’t bother you, then JPMorgan Chase ($JPM) is a strong buy.

That’s all for now. The stock market will be closed on Monday for Labor Day. Next week, we’ll get some important economic reports, such as the ISM and productivity reports, and the big jobs report comes next Friday. Be sure to keep checking the blog for daily updates. I’ll have more market analysis for you in the next issue of CWS Market Review!

– Eddy

-

Morning News: August 31, 2012

Eddy Elfenbein, August 31st, 2012 at 6:48 amGermany Plays Bad Cop as Irish Chase Bank Debt Help

EU Plan Said to Give ECB Sole Power to Grant Bank Licenses

Euro Zone Inflation Jumps, Weighs On Rate Cut Bets

Apple Loses Patent Lawsuit Against Samsung in Japan

Qatar’s Rejection Leaves Glasenberg to Decide on Xstrata

Majority of New Jobs Pay Low Wages, Study Finds

Bernanke May Hint At QE Without Boxing Fed In

Corporate Bond Sales Top $237 Billion in Record August

Hermes Raises Growth Target as China Demand Boosts Sales

Tata Motors Finds Success in Jaguar Land Rover

Russia’s Berezovsky loses UK battle with Abramovich

Credit Writedowns: Peak Oil: Light Sweet Crude Production Has Peaked Globally

Be sure to follow me on Twitter.

-

“American Investors Lack Basic Financial Literacy”

Eddy Elfenbein, August 30th, 2012 at 7:23 pmI recently wrote about the comics and games put out by the Federal Reserve. I concluded that unfortunately, many Americans need these types of materials because they know nothing about managing their money.

One provision of the Dodd-Frank Act was to look at American financial literacy. The report came out today…and we got a big fat F. Here’s a depressing quote:

According to the Library of Congress report, studies consistently show that American investors lack basic financial literacy. For example, studies have found that investors do not understand the most elementary financial concepts, such as compound interest and inflation. Moreover, many investors do not understand other key financial concepts, such as diversification or the differences between stocks and bonds, and are not fully aware of investment costs and their impact on investment returns. According to the Library of Congress report, studies show that investors lack critical knowledge that would help them protect themselves from investment fraud. In particular, surveys demonstrate that certain subgroups, including women, African-Americans, Hispanics, the oldest segment of the elderly population, and those who are poorly educated, have an even greater lock of investment knowledge than the average general population. The Library of Congress Report concludes that “low levels of investor literacy have serious implications for the ability of broad segments of the population to retire comfortably, particularly in an age dominated by defined-contribution retirement plans.” Furthermore, it states that “intensifying efforts to educate investors is essential,” and that investor education programs should be tailored to specific subgroups “to maximize their effectiveness.”

What’s left unsaid is that it’s in Wall Street’s best interest to keep folks in the dark.

-

The Fed Gathers in Jackson Hole

Eddy Elfenbein, August 30th, 2012 at 2:10 pmThis week, the Federal Reserve gathers at its annual Labor Day weekend retreat in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Investors all over the world are ready to hear news that could, just maybe, just possibly, be important.

But probably not.

Gary Alexander explains why Jackson Hole has become important:

During Bernanke’s speech at Jackson Hole on August 27, 2010, hefirst acknowledged that the pace of economic growth had been “less vigorous” than the Fed was expecting and that the pace of the U.S. job growth had been “painfully” slow. Bernanke also acknowledged that the Fed was surprised by the “sharp deterioration” in the U.S. trade balance. His solution was to revive 2008’s “quantitative easing” as “QE-2.” The market loved QE-2: The S&P 500 rose from 1040 on the day of Bernanke’s 2010 Jackson Hole talk to 1363 the following April – up 30% in eight months.

At Jackson Hole in 2011, Chairman Bernanke laid the groundwork for another monetary strategy called “Operation Twist.” Over the next few weeks, various Fed governors hit the road to explain and defend their $400 billion operation to artificially flatten the yield curve. The stock market also liked Operation Twist. The S&P 500 rose from 1099 to 1419 in the six months from October 3, 2011 to April 2, 2012. (A clear improvement in various economic indicators also helped!)

So if it made headlines the last two years, it most certainly will again this year? Well, I doubt it.

Under Bernanke, the Fed has become slightly more transparent. The central bank is still very opaque, but some rays of light have been allowed through.

The Fed has been surprisingly forthright about its intentions, and this time around, they seem pretty clear that more action will not be needed. In fact, most economic news aides the case for inaction. And let’s not forget that a general election is only weeks away so the Fed will try to avoid any signs of partisanship.

I’m not expecting much news out of Jackson Hole.

-

Amazon Touches $250

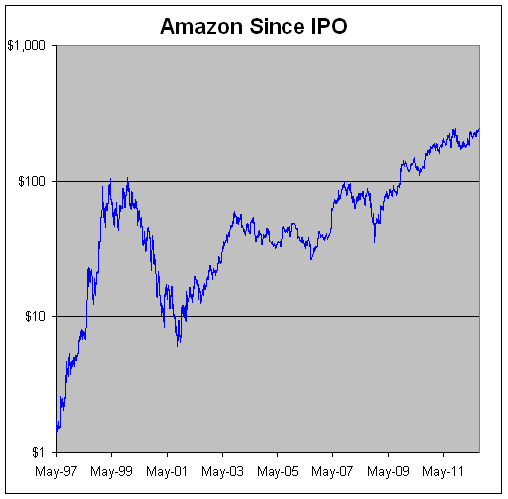

Eddy Elfenbein, August 30th, 2012 at 11:31 amEarlier today, shares of Amazon.com ($AMZN) finally touched $250. That’s an astounding run since the comapny’s IPO more than 15 years ago. What’s interesting is even if bought Amazon at its 1999 peak of $113 per share and held on, you would have more than doubled your money 13 years later. The S&P 500, by contrast, is still down.

The problem, of course, is the “and hold on” part. Would you have been able to watch your initial investment at $113 plunge all the way down to $5.51 as Amazon did after 9/11? I doubt I could.

Wall Street currently expects Amazon to earn $2.38 per share next year. That means the stock is going for 105 times earnings. I don’t think this will end well.

-

Morning News: August 30, 2012

Eddy Elfenbein, August 30th, 2012 at 8:10 amEuro-Area Confidence Drops, German Jobless Increases

ECB Action Prospects Underpin Italian Bond Auction

ICBC Profit Growth Slips to 11% as China Slowdown Hits Loans

China to Continue Investing in Europe

Gold Holds Steady Ahead of Jackson Hole Symposium

U.S. Q2 Growth Revised Up, Fed Still Seen in Play

Mortgage Settlement With Banks Starts To Ease Foreclosure Crisis

Hedge Fund Proposal Would Allow Secretive Enclave to Open Up

Costco, Limited Exceed August Sales Estimates

GSV Capital, Placing Bets on Start-Ups, Falters

Citigroup Agrees To Pay $590 Million In Shareholder Suit

Sears Holdings Exiting S&P 500

Joshua Brown: An Asset Allocator’s Prayer

Howard Lindzon: The Web and Google are Winning…Facebook and Twitter are only #Winning

Be sure to follow me on Twitter.

-

JoS A Bank Soars on Strong Earnings

Eddy Elfenbein, August 29th, 2012 at 3:35 pmFor the second time this week, one of our Buy List stocks is soaring. And for the second time, it was one of the stocks I had been down on.

This morning, JoS. A. Bank Clothiers ($JOSB) reported quarterly earnings of 83 cents per share for its fiscal second quarter. That was 10 cents per share more than Wall Street had been expecting. The metric is that same-store sales were up 6.1%. The company did especially well with its online sales.

JoS A Bank, which competes with Men’s Wearhouse Inc, has set up Amazon.com Inc and eBay Inc stores, aiming for a bigger slice of shoppers’ wallets by catering to different consumers than the ones who come to their own websites and physical stores.

Sales at its direct marketing segment, which comprises the Internet and catalog call centers, rose 39.3 percent for the second quarter. The segment recorded higher sales in August compared to last year, the company said.

Direct marketing, driven primarily by Internet sales, accounted for about 10 percent of total sales last year.

Several retailers are looking to grow into the online market place by setting up storefronts on Amazon and eBay.

JoS A Bank also signed up for PayPal’s in-store service in May that allows shoppers to pay through their mobile phones, making purchases at brick-and-mortar stores easier.

Comparable store sales increased 6.1 percent for three months ended July 28. Total sales rose 12.9 percent to $260.3 million.

In last week’s CWS Market Review, I expressed my frustration with JoS. A. Bank. I even said that adding it to this year’s Buy List was a mistake. This is why I don’t try to time the market. Though in my defense I did say that the stock wasn’t unreasonably priced at $41.

At one point today, the stock was up 18.76%, and that doesn’t include the stock’s 3.51% rally yesterday. JOSB has settled down some and it’s currently up just over 14%. Of course, much of today’s gain is merely walking back losses from earlier in the year. As of now, JOSB is down just over 2% for the year.

-

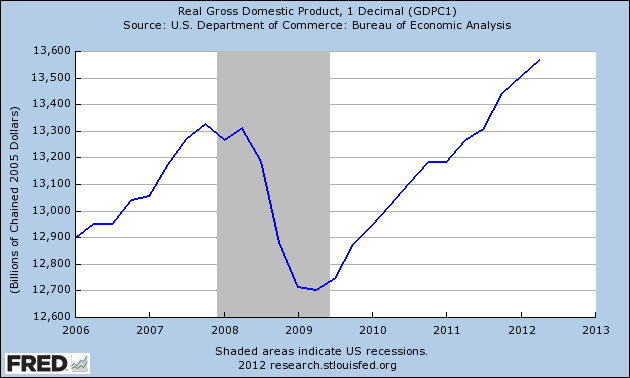

Q2 GDP Growth = 1.7%

Eddy Elfenbein, August 29th, 2012 at 11:15 amThe economy had some good news, and it’s slightly more evidence in favor of our the-economy-is-stronger-than-people-realize thesis. The government revised higher its estimate for second quarter GDP growth.

The initial estimate one month ago said the economy grew by 1.5% during the second quarter. Now they’re saying it was 1.7%. Sure, that’s not a major revision but at least it’s in the right direction.

A second straight quarter of slowing growth shows the world’s largest economy is having difficulty making headway as consumers stay frugal and looming tax changes prompt companies to limit investment and hiring. Chairman Ben S. Bernanke this week may reaffirm the view of many Federal Reserve policy makers that more stimulus will be needed unless the expansion shows signs of strengthening.

“We are very much struck in a slow-growth mode,” said Mark Vitner, a senior economist at Wells Fargo Securities LLC in Charlotte, North Carolina, who correctly forecast the revision. “We still don’t see the economy breaking free of this 1.5 percent to 2 percent growth rate. A 1.7 percent pace is the personification of the Fed’s frustration.”

The economy grew by 2% in the first quarter. Before today’s data came out, we were able to say that economic growth was “decelerating,” meaning rate of growth was slowing. That’s still technically true, but it’s probably more accurate to say that growth has leveled off during the first half of this year.

-

-

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His