Are We in a Bubble?

The latest rage on Wall Street is to pronounce that stocks are in a bubble. This is rather unusual in that true bubbles are very rare. This is, of course, different from stocks dropping in a routine lousy market. That happens every few years.

Do I think that stocks are in a bubble? Honestly, I don’t know. And more importantly, I don’t much care. Let me explain.

For one, it’s odd to make a judgment about the aggregation of 6,000 publicly traded stocks. Our Buy List is pretty well diversified and that’s just 20 stocks. Where the entire S&P 500 is headed isn’t that important for a disciplined stock picker.

Also, even if the market is about to plunge, it’s very difficult to get the timing just right. Lots of people saw the housing bubble but they were very early. The bubble kept on going. Recently I noted that if an investor bought an S&P 500 index fund just prior to the Financial Crisis, say in March 2008, and held on to today, they would have made a decent return by historical standards. Time may not heal investing wounds, but it sure can help a lot.

When looking at valuation metrics, I urge investors to look at as many as they can, but never be a slave to just one. I’m particularly leery of metrics like the Cyclically Adjusted P/E ratio, also known as CAPE. The CAPE looks at the stock market’s current value weighted against the last ten years of earnings. The idea is to smooth out the economic cycles. I think this is a bad idea because stocks and earnings are themselves cyclical.

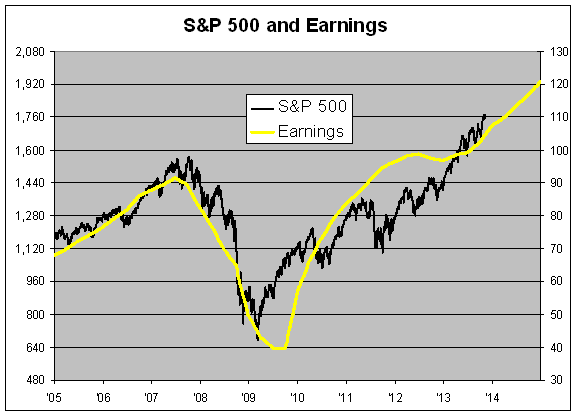

Also, the inclusion of so much prior data is, in my opinion, an unfair anchor to carry. The historic plunge in corporate earnings in 2008-09 will still be a part of CAPE for another five years. If we look at operating earnings or dividends, we can see what an outlier that profit data is. Interestingly, the market’s dividend yield has remained fairly consistent for the last decade, except for the worse parts of the Financial Crisis.

After two of the biggest bear markets in history is precisely when so many people are scared of another bubble. I’m reminded of people saying that shortly after 9/11 was actually the safest time to fly. Bubbles are now, apparently, everywhere.

I think the best way to look at the issue is to divide bear markets into two categories. One is where price shoots far above value. That’s your classic bubble ala 1987 or 2000. The second is when value crumbles beneath price. That happened in 1990 and 2008.

You might be surprised to hear me say that 2008 wasn’t a bubble. That’s right; stock valuations really weren’t that excessive. It was the fundamentals that turned out to be terrible. Believe it or not, stock valuations were above average in 1929, but not out of sight. The frothiest part of the bull market occurred in the last six months. The 1920s was not a decade of stock euphoria.

I think there’s a natural tendency to reverse engineer a narrative that the world was enthralled to greed and everyone bought stocks without thought. That describes the feeling about Tech stocks in 1999, but it’s not an accurate description of today’s environment. The S&P 500 is going for about 17 times this year’s earnings. That’s about normal. The P/E Ratio has risen over the last two years, but it’s really gone from low to average, not from normal to nose-bleed territory.

Analysts currently estimate that the S&P 500 will earn $120 per share next year. Now’s the time for skepticism. For one, analysts don’t have a great forecasting track record. The critical question is, could fundamentals soon fall apart? Are there hidden factors that might make the S&P 500 earnings, say, $90 or even less next year? This is the question to worry about.

It’s also hard to predict things that are unexpected because, well, they’re not expected. If they were expected, they probably would be much less interesting. Also, it’s the unexpectedness of an event that makes it important.

The things that worry me are the things we aren’t thinking about. For one, corporate profit margins are very high. I think it’s reasonable to expect that earnings growth will be below economic growth over the next several years. Though the high profit margins probably aren’t a reflection of corporate greed, rather they’re a natural byproduct of slow growth and low interest rates.

Earnings recessions generally don’t announce themselves beforehand, but there are some useful warning signs. One good indicator is the yield curve. When short-term rates rise above long-term rates, the economy often runs into trouble soon after. For now, the yield curve is far from inverted.

Another late cycle indicator is rising inflation. According to the latest numbers, that’s not a problem either. I also like to follow the monthly ISM reports. A reading below 45 is often a sign of trouble. Once again, we’re in the safe zone.

(You can sign up for my free newsletter here.)

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on November 11th, 2013 at 10:44 am

The information in this blog post represents my own opinions and does not contain a recommendation for any particular security or investment. I or my affiliates may hold positions or other interests in securities mentioned in the Blog, please see my Disclaimer page for my full disclaimer.

- Tweets by @EddyElfenbein

-

-

Archives

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His