-

The Huckabee Portfolio

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 11th, 2007 at 6:06 pmNothing terribly interesting. Though on page three, he misspelled Procter & Gamble (PG). Also, the “e” in Home Bancshares (HOMB) is a bit faded. When I first saw it, I thought he owned Homo Bancshares.

That probably wouldn’t help in Iowa. -

“At Least”

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 11th, 2007 at 5:16 pmShares of General Electric (GE) fell sharply today, even more than the rest of the market, after the company forecast earnings growth of 10% for next year.

There was one widdle biddy problem. The press release left out the words “at least.”

Oopsie!

The stock dropped quickly 4.75% or roughly $18 billion.

The company rushed to clarify that it’s looking to grow EPS by at least 10% next year, which makes more sense. Check out the words “or better” at the top of this press release. GE was playing the typical Wall Street game of lowering expectations.

By the way, when you talk about GE’s numbers you’re really in a different universe. For Q4, GE is looking for 67 to 69 cents a share. Well, those two pennies translate to….

**Dr. Evil Voice**

Two Hundred MILLION Dollars

Mwahahaha -

The Fed Cuts By 0.25%

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 11th, 2007 at 2:15 pmHere’s the statement:

The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to lower its target for the federal funds rate 25 basis points to 4-1/4 percent.

Incoming information suggests that economic growth is slowing, reflecting the intensification of the housing correction and some softening in business and consumer spending. Moreover, strains in financial markets have increased in recent weeks. Today’s action, combined with the policy actions taken earlier, should help promote moderate growth over time.

Readings on core inflation have improved modestly this year, but elevated energy and commodity prices, among other factors, may put upward pressure on inflation. In this context, the Committee judges that some inflation risks remain, and it will continue to monitor inflation developments carefully.

Recent developments, including the deterioration in financial market conditions, have increased the uncertainty surrounding the outlook for economic growth and inflation. The Committee will continue to assess the effects of financial and other developments on economic prospects and will act as needed to foster price stability and sustainable economic growth.Frickin wimps.

There was one dissension. Eric S. Rosengren wanted a 50-basis-point cut.

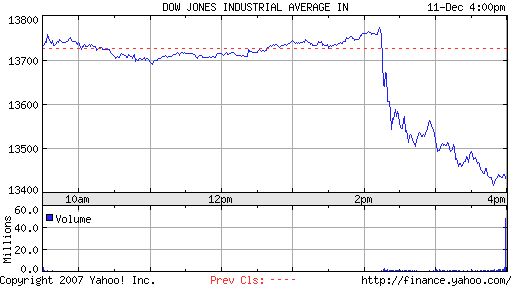

Update: The market’s verdict is in and it’s not pleased:

Think you can tell when the rate cut was? I bet you can. -

Derivative Trades Jump 27% to Record $681 Trillion

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 11th, 2007 at 11:16 amFrom Bloomberg:

Derivatives traded on exchanges surged 27 percent to a record $681 trillion in the third quarter, the biggest increase in three years, the Bank for International Settlements said.

Interest-rate futures, contracts designed to speculate on or hedge against moves in borrowing rates, led the increase with a 31 percent increase to $594 trillion during the three months ended Sept. 30, the Basel, Switzerland-based BIS said today in its quarterly review. The amounts are based on the notional amount underlying the contracts.

Trading surged as investors bet on losses linked to record U.S. mortgage foreclosures and policy changes by the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank to offset the credit slump. The Fed cut its benchmark interest rate by half a point to 4.75 percent in September, the central bank’s first reduction in four years. -

UNH Hits 52-Week High

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 11th, 2007 at 10:14 amHere are some random thoughts I had this morning.

Perhaps it’s me, but I seem hear a lot of commentators speaking as if the market were going through some great reckoning; as if years of wild speculation is finally being punished. Sure, folks who owned Citigroup (C) or Countrywide (CFC) or Fannie Mae (FNM) are going through rough times, but that’s hardly true for the market as a whole. Including dividends, the S&P 500 is up 8% for the year. That’s about spot on for the historical average. We’re only 3.5% off the all-time high reached two months ago. Swing by your local bank and see if you can find an 8% CD.

I also see that UnitedHealth Group (UNH) finally made a new 52-week high. The stock is above $58 for the first time since March 2006. Man, what the hell took it so long? UNH generates two things, huge profits and awful headlines. Investors, apparently, only pay attention to one. Just a few weeks ago, UNH said it was projecting EPS for 2008 of $3.95 to $4. This isn’t buried news—it’s public information, yet it’s taking a long time to sink in.

A Banc of America analyst just initiated coverage of Danaher (DHR) with a buy rating, a $100 price target and he called it his top buy in the sector.

Lastly, here’s a great look at AFLAC (AFL) from Standard & Poor’s. -

Felix Salmon Issues a Plea

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 10th, 2007 at 11:07 amAs usual, Felix nails it:

Please can the punditosphere stop referring to the mortgage-freeze plan as a “bailout”? As Edmund Andrews says in his first sentence on the front page of the NYT today, it isn’t. The FHA’s FHASecure plan, which has existed for ages, might conceivably be considered a bailout. This one involves no government money or government guarantees, and there’s no transfer of funds from the taxpayer to anybody at all. So it’s not a bailout. Thank you.

He’s right. There’s zero public money at stake. The LTCM bailout of 1998 is also often referred to as a bailout. In fact, I just did. The Federal Reserve helped organize it, but no government money was involved. As someone who often criticizes the Fed, that’s exactly what they should have done.

-

Portfolio’s Scoop: There Are These Things Called Index Funds

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 10th, 2007 at 10:16 amI just finished a puzzling 7,000-word article by Michael Lewis for the December issue of Portfolio (The Evolution of an Investor).

The article is about efficient markets—the idea that it’s impossible for a stock-picker or mutual fund to consistently beat the market. Lewis uses the story of Blaine Lourd, a former stock-broker, as the vessel for his article.

The problem is, the idea of efficient markets was popularized 34 freakin’ years ago by Burton Malkiel in “A Random Walk Down Wall Street.” It’s only gone through about a gazillion printings. The original academic paper by Eugene Fama appeared in 1965. Everyone and his brother knows about it. What’s this article doing in a business magazine in 2007? It would be roughly the equivalent of an article on this new-fangled designated hitter rule appearing—mind you, not in Reader’s Digest or People—but in Sports Freakin’ Illustrated!

Does Portfolio think its readers are that ill-informed?

The article doesn’t even present the arguments for and against EMH in any real depth, which could be a more interesting article. In fact, an article attacking EMH would also feel at least 10 years out of date. Closer to 15.

Lewis doesn’t bother touching topics like the gradations of EMH (weak, strong and semi-strong). The frustrating part is that there are lots of interesting angles that could have been explored. Lewis could have discussed developments in fields like behavioral finance and their possible implications for EMH. Or the success of quant guys like Jim Simons. Fuck, even I wrote a post the other day about the astonishing success of momentum stocks, and I’m just an obscenity-using blogger. I mean, what the fuck?

Lewis also conflates the idea of being a good money manager with picking stocks. Money managers do a lot more than that. At least, they should. For example, they may help a client with an investment for a specific time horizon like a college fund. A money manager also helps decide an appropriate risk profile for the client, or how to keep taxes down, or how to plan for retirement. It’s a gross simplification to say these people are worthless because they can’t pick stocks. From personal experience, there were lots of times I talked clients out of exiting the market.

I also have issues with the story of Blaine Lourd, the stock-broker turned cynic turned EMH convert. I don’t think he’s lying, but I get the feeling that Lourd is overscripting his conversion story. Cynical people who grow frustrated by their industries don’t act as Lourd does. Put it this way: He managed his self-loathing well enough to hop to three more firm firms, then to open his own shop in Beverly Hills. If Lourd’s mission is to protect investors, then I wonder who’s covering his rent?

Lewis centers the article on the unusual training ritual (or indoctrination) of indexer Dimensional Fund Advisors. The firm has done very well over the years particularly by pointing out that most mutual funds don’t beat the market. But wouldn’t that mean that the firm’s success is due to a gross inefficiency in the market? Or is that too impolite to ask. Apparently, it is because Lewis never asks it. Nor does he ask any tough follow-up questions.

Later, Professor Fama, a DFA board member, makes an appearance:Forty years of preaching has taught him that his audience either agrees with him or never will. And so he speaks dully, like a man talking to himself. But he makes his point. In his years of researching the stock market, he has detected only three patterns in the data. Over the very long haul, stocks have tended to outperform bonds, and the stocks of both small-cap companies and companies with high book-to-market ratios have yielded higher returns than other companies’ stocks.

These are the facts. The question is how to account for them. Fama’s explanation is simple: Higher returns are always and everywhere compensation for risk. The stock market offers higher returns than the bond market over the long haul only because it is more volatile and thus more risky. The added risk in small-cap stocks and stocks of companies with high book-to-market ratios must manifest itself in some other way, as they are no more volatile than other stocks. Yet in both cases, Fama insists, the investor is being rewarded for taking a slightly greater risk. Hence, the market is not inefficient.Wait a second. High book-to-market stocks outperform with no more volatility but that’s due to higher risk? OK, so where is this risk? C’mon Michael, we just saw evidence disproving the whole point of the article. How does Fama support his assertion?

Lewis concludes the article with this:Blaine still takes great pleasure in describing just how screwed up the American financial system is. “In a perfect world, there wouldn’t be any stockbrokers,” he says. “There wouldn’t be any mutual fund managers. But the world’s not perfect. In Hollywood, especially, people need to believe there’s a guy. They say, ‘I got a friend who made 35 percent last year.’ Or ‘What about Warren Buffett?’ ”

Then he pulls out a chart. He graphs for me the performance of one of D.F.A.’s value funds, which consists of companies with high book-to-market ratios, against the performance of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway since 1999. While Buffett’s line rises steadily, D.F.A.’s rises more steeply. Blaine’s new belief in the impossibility of beating the market doesn’t just beat the market. It beats Warren Buffett.That doesn’t prove any point. Buffett has still beaten the market as whole. It’s that value stocks have done much better. Why are we changing the thesis of the entire story and now comparing Buffett to a value fund? We’re not allowed to pick stocks but we can pick benchmarks? To reiterate my earlier point, what the fuck? Lewis’ article is presented to us as if it’s delivering some wise truism, yet it fails to ask any truly probing questions.

When Portfolio debuted, Elizabeth Spiers of DealBreaker said it “will be the Paris Hilton of business magazines: pretty but vapid, and unlikely to produce anything resembling an original thought.” Perhaps some forecasts do have value. -

Hip Hop IPO

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 10th, 2007 at 9:53 amLuther Campbell, the creative force behind 2 Live Crew and some of their timeless melodies such as The Fuck Shop, Get the Fuck out of My House and I Ain’t Bullshittin, has taken his company public.

The New York Post reports:The hip-hop legend – personally responsible for the “Parental Warning” on CDs thanks to the rebellious and outlandish lyrics on his group’s 2 Live Crew discs – has merged his entertainment and sports management company into a public shell company that’s now listed on Nasdaq.

Luke Entertainment Group, ticker symbol LKEN, started trading last month.

“Going public gives me more freedom and a better opportunity,” says Campbell, 46, who’s known in the music industry as Luke Skyywalker.

Campbell, who will serve as Chief Creative Officer, hopes to mimic other so-called 360 deals like the one Live Nation recently inked with Madonna. That is, to represent talent in more than just record deals but in concert promotion, tour management and in other areas.Hmmm. I have to say I’m not terribly impressed by someone who adds an extra “y” to Skywalker being the Chief Creative Officer. The article notes that the stock closed yesterday at $1.

(Via: The Stalwart). -

God, Money and the New York Times

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 9th, 2007 at 3:04 pmThis is from the New York Times’ editorial on Mitt Romney’s recent speech:

Mr. Romney dragged out the old chestnuts about “In God We Trust” on the nation’s currency, and the inclusion of “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance — conveniently omitting that those weren’t the founders’ handiwork, but were adopted in the 1950s at the height of McCarthyism.

That’s not quite right. The motto “In God We Trust” first appeared on U.S. coins during the Civil War. Although there have been periods when it was removed, the motto has appeared on all U.S. coins for nearly 100 years.

The motto was later added to U.S. paper currency in October 1957, which wasn’t exactly “the height of McCarthyism,” considering that the senator had been dead for five months.

The Treasury Department’s website has the details. -

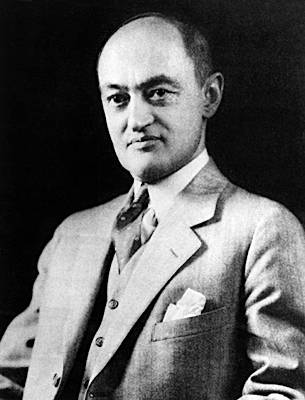

Prophet of Innovation: Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on December 7th, 2007 at 3:35 pm

Brad Delong reviews Thomas K. McCraw’s Prophet of Innovation: Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction:Over the previous two and a half centuries, three different economic worldviews, in succession, reigned. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Adam Smith’s was the key economic perspective, focusing on domestic and international trade and growth, the division of labor, the power of the market, and the minimal security of property and tolerable administration of justice that were needed to carry a country to prosperity. You could agree or you could disagree with Smith’s conclusions and judgments, but his was the proper topical agenda.

The second reign was that of David Ricardo and Karl Marx. Their preoccupations dominated the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They worried most about the distribution of income and the laws of the market that made it so unequal. They were uneasy about the extraordinary pace of technological, organizational, and sociological change, and about whether an ungoverned market economy could produce a distribution of income — both relative and absolute — fit for a livable world. Again, you could agree or disagree with their judgments about trade, rent, capitalism, and machinery, but they asked the right questions.

The third reign was that of John Maynard Keynes. His agenda dominated the middle and late 20th century. Keynes’s theories centered on what economists call Say’s Law — the claim that except in truly exceptional conditions, production inevitably creates the demand to buy what is produced. Say’s Law supposedly guaranteed something like full employment, except in truly exceptional conditions, if the market was allowed to work. Keynes argued that Say’s Law was false in theory, but that the government could, if it acted skillfully, make it true in practice. Agree or disagree with his conclusions, Keynes was in any case right to focus on the central bank and the tax-and-spend government to supplement the market’s somewhat-palsied invisible hand to achieve stable and full employment.

B ut there ought to have been a fourth reign, for there was a set of themes not sufficiently explored. That missing reign was Schumpeter’s, for he had insights into the nature of markets and growth that escaped other observers. It is in that sense that the late 20th and early 21st centuries in economics ought to have been his: He asked the right questions for our era.

-

-

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His